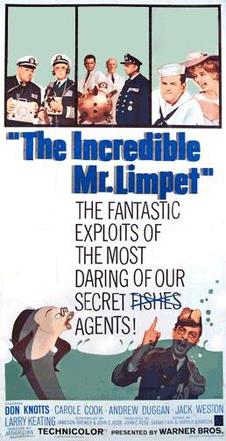

1964

Directed by Arthur Lubin

Welcome back to Movie Monday, where we continue our masochistic descent through the depths of my personal cinematic hell. As always, my standard disclaimer applies: this list represents one person’s highly subjective opinions, shaped by peculiar tastes and specific experiences that may have absolutely nothing to do with your own. What I consider unwatchable dreck might be the movie that defined your childhood Saturday afternoons, the film that introduced you to Don Knotts, or the VHS tape that occupied permanent residence in your family’s player throughout the 1980s. If you hold The Incredible Mr. Limpet close to your heart, I’m not here to invalidate that affection—I’m just here to explain why I can’t share it.

This week brings us to number 36: The Incredible Mr. Limpet, a 1964 live-action/animated hybrid that asked audiences to believe Don Knotts could turn into a fish and help win World War II. Yes, you read that correctly. This is a real movie that real people made with real money and real conviction that this premise would work.

My Journey to the Bottom of the Ocean

I first encountered The Incredible Mr. Limpet sometime in the mid-1980s, almost certainly on TBS during one of their interminable blocks of pre-1970 programming. This was the era when Ted Turner’s superstation seemed to have the broadcast rights to exactly seventeen movies, which they cycled through on an endless loop. If you watched TBS with any regularity during this period, you inevitably became intimately familiar with whatever Don Knotts vehicles they happened to own.

I’m reasonably certain The Incredible Mr. Limpet was paired with The Ghost and Mr. Chicken, because apparently the programming philosophy was “if you’re going to subject children to one Don Knotts movie, why not make it two?” It’s the double-feature equivalent of getting chicken pox—once you’re exposed, you might as well get the full experience.

I was probably around eight or nine years old, an age when I should have been the target demographic for this kind of whimsical fantasy. Instead, even my underdeveloped critical faculties recognized something deeply wrong with what I was watching. It wasn’t just that the movie was weird—plenty of great movies are weird. It was that the movie was weird in a way that felt fundamentally broken, like someone had taken three different film concepts and mashed them together without checking whether they were compatible.

Fast-forward to my recent rewatch in preparation for this post, and I’m sad to report that forty-something me finds the film no more coherent or enjoyable than eight-year-old me did. If anything, adult perspective has only sharpened my understanding of exactly why this movie doesn’t work.

The Don Knotts Problem (Again)

Let me start by saying something I’ve said before in these pages, most recently in my evisceration of The Apple Dumpling Gang: Don Knotts is a comedic genius when deployed correctly. As Barney Fife on The Andy Griffith Show, he created one of television’s most iconic characters—nervous, well-meaning, perpetually in over his head, and absolutely perfect as Andy Griffith’s comedic foil. Knotts won five Emmy Awards for that role, and every single one of them was deserved.

But here’s the thing about Barney Fife: he works because he’s the sidekick. He’s the comic relief character who gets to be funny in measured doses while the actual protagonist provides stability and perspective. Knotts’s twitchy energy, bug-eyed reactions, and physical comedy are the seasoning that makes the main dish better—but you can’t make an entire meal out of seasoning.

The Incredible Mr. Limpet asks Don Knotts to carry a feature film as the lead character, and the cracks show almost immediately. As Henry Limpet, the mild-mannered bookkeeper who loves fish more than seems psychologically healthy, Knotts employs all his usual tricks: the nervous stammering, the physical timidity, the exaggerated reactions. For the first twenty minutes, when Limpet is still human, it’s tolerable if uninspired. But then Limpet transforms into a fish, and the movie faces an impossible challenge: how do you translate Don Knotts’s physical comedy into animation?

The answer, unfortunately, is “poorly.”

The Animation Catastrophe

The Incredible Mr. Limpet was produced during the twilight years of Warner Bros. Cartoons, and it shows. This was literally the final project for the studio before its temporary closure in May 1963, and you can almost feel the animators’ exhaustion seeping through every frame.

The animated sequences were supervised by Robert McKimson, a legitimate legend who had worked on classic Looney Tunes for decades. But there’s a vast difference between animating Bugs Bunny outsmarting Elmer Fudd in seven minutes and animating a fish wearing glasses having an existential crisis across an hour of screen time. The animation here isn’t terrible by 1964 standards—it’s competent in a workmanlike way—but it’s nowhere near inventive or charming enough to compensate for the fundamental absurdity of the premise.

When live-action/animation hybrids work—and they can work beautifully, as Mary Poppins proved the same year—it’s because the filmmakers understand that the animated segments need to operate by different rules than reality. Mary Poppins used animation to create a sense of whimsy and impossible magic. Who Framed Roger Rabbit (admittedly much later, in 1988) used it to create a fully realized parallel world with its own internal logic.

The Incredible Mr. Limpet uses animation because… well, because they needed to show Don Knotts as a fish, and makeup wasn’t going to cut it. The animated sequences exist purely as a technical necessity rather than an artistic choice, and it shows. There’s no real visual imagination on display, no sense that the underwater world operates by dream logic or heightened reality. It’s just… fish. Swimming. Occasionally talking. While wearing glasses.

Those glasses, by the way, deserve their own paragraph of mockery. Henry Limpet’s defining physical characteristic is his pince-nez spectacles, which he continues to wear after his transformation into a fish. The film never explains how glasses work underwater, how they stay on a fish that has no ears or nose bridge, or why a fish would even need corrective lenses. They’re there purely as a visual identifier so the audience can tell which fish is the one that used to be Don Knotts, which suggests the animators didn’t have enough confidence in their character design to make him recognizable without a prop.

The Premise That Couldn’t Possibly Work

Let’s talk about the plot, shall we?

Henry Limpet is a meek bookkeeper in Brooklyn who is obsessed with fish. Not in a “I enjoy aquariums” way, but in a “this might require professional intervention” way. His wife Bessie (Carole Cook) is understandably frustrated with his ichthyological fixation, especially since we’re on the brink of World War II and Limpet seems more concerned with marine life than the fate of the free world.

Limpet’s friend George (Jack Weston) is a machinist’s mate in the Navy, which makes Limpet desperate to enlist so he can serve his country. Unfortunately, Limpet is classified 4-F due to his poor eyesight and presumably several other physical inadequacies the film is too polite to specify. Rejected and dejected, Limpet visits Coney Island with George and Bessie, where he falls off a pier and—through mechanisms the film never bothers to explain—transforms into a fish.

Not just any fish, mind you, but a talking fish. With glasses. And the ability to produce a powerful sonic weapon called a “thrum” that can be used to locate and destroy Nazi submarines.

I want to pause here and acknowledge that I understand this is a fantasy film. I’m not demanding rigorous scientific explanation for the transformation—The Metamorphosis doesn’t explain how Gregor Samsa became a bug, and that’s not a problem. But Kafka’s story works because it’s clearly operating as allegory and nightmare logic. The Incredible Mr. Limpet wants to have it both ways: it wants the whimsy of a fairy tale transformation but also wants to ground itself in the real historical context of World War II and actual naval strategy.

This tonal inconsistency permeates the entire film. Are we watching a silly fantasy about a fish who helps the Navy? Or are we watching a genuine war film that happens to feature animation? The movie can never decide, lurching awkwardly between goofy underwater antics and somber scenes of naval officers strategizing about the Battle of the Atlantic.

The Romantic Subplot Nobody Needed

As if the premise weren’t already overstuffed, the film decides that fish-Limpet needs a love interest. Enter Ladyfish (voiced by Elizabeth MacRae), a female fish who Limpet rescues and promptly falls in love with, despite the minor complication that he’s already married to a human woman back in Brooklyn.

The film treats this interspecies, extra-marital romance with baffling earnestness. Limpet genuinely seems to develop romantic feelings for Ladyfish, and the movie presents this as sweet rather than deeply disturbing. There’s no indication that Limpet feels guilty about emotionally abandoning his wife, no sense that the film recognizes the fundamental weirdness of a former human falling in love with an actual fish.

By the end of the film, when Limpet gets a chance to say goodbye to Bessie, she gives him a replacement pair of glasses (the Nazis destroyed his original set—long story), and Limpet swims off with Ladyfish to live happily ever after. Bessie’s reaction is basically “oh well, I guess my husband is a fish now and has a fish girlfriend, that’s fine.” The film presents this as a happy ending rather than a tragedy of transformation and loss.

Compare this to other transformation narratives, even silly ones. In Disney’s The Little Mermaid, Ariel’s transformation involves genuine sacrifice and the story acknowledges the cost of leaving one world for another. Here, Limpet gets to abandon his human life, his human wife, and all his human responsibilities without any real consequences or emotional complexity.

The War Effort Angle

The film’s treatment of World War II is perhaps its strangest element. The Incredible Mr. Limpet wants credit for being a patriotic war film—Limpet helps the Navy locate and destroy German U-boats, playing a significant role in the Allied victory in the Battle of the Atlantic. The film includes actual naval vessels, military procedures, and references to real historical events.

But it’s hard to take any of this seriously when the secret weapon is a fish that goes “thrum.”

There’s something deeply uncomfortable about using the backdrop of actual war—a conflict in which real people died—as the setting for a whimsical comedy about a cartoon fish. The tone-deafness is remarkable. We’re supposed to find it funny when Limpet outsmarts Nazi submarine commanders, but we’re also supposed to be invested in the genuine stakes of the Battle of the Atlantic. The film wants the gravitas of a war picture and the frivolity of a cartoon, and ends up achieving neither.

The coda, set in 1963, suggests that Limpet has been teaching porpoises his techniques, which the Navy wants to utilize. This feels like the film trying to tie itself to contemporary military research (the Navy did actually study marine mammals), but it just adds another layer of tonal confusion. Are we in a realistic world where the military studies dolphin intelligence, or a fantasy world where men turn into fish? Pick one.

The Failed Remake Saga

It’s worth noting that Hollywood has been trying to remake The Incredible Mr. Limpet for nearly three decades, which suggests somebody believes there’s value in this concept. The project has attracted an impressive roster of talent over the years: Jim Carrey was attached in the late 1990s, with roughly $10 million spent on animation tests to digitally map Carrey’s face onto a fish body (producing “disastrous results,” according to reports). Directors Mike Judge and Richard Linklater both signed on at different points. Actors including Robin Williams, Chris Rock, Mike Myers, Adam Sandler, and Zach Galifianakis were considered for the lead role.

None of these attempts came to fruition, and I suspect I know why: the fundamental premise doesn’t work. You can update the animation, modernize the setting, cast contemporary comedy stars—but you’re still left with a movie about a man who turns into a fish and helps fight a war. That’s not a premise that’s been waiting for better technology to realize it properly. It’s a premise that’s fundamentally flawed, a relic of a particular moment in 1960s family entertainment that doesn’t translate to modern sensibilities.

The fact that Don Knotts himself supported the remake idea (mentioned in his autobiography) is sweet but doesn’t change the underlying problem. Knotts was a gracious, humble performer who always seemed surprised by his own success. Of course he’d be supportive of others trying to reinterpret his work. But supporting something doesn’t make it a good idea.

Why The Incredible Mr. Limpet Earns Its Spot at Number 36

The Incredible Mr. Limpet lands at number 36 on my worst movies list not because it’s incompetently made—the technical aspects are adequate for 1964—but because it represents a particular kind of misguided ambition. This is a film that thought it could combine Don Knotts comedy, Warner Bros. animation, World War II naval strategy, and a cross-species romance into something coherent and entertaining.

It couldn’t.

The film fails at multiple levels simultaneously. It fails as a Don Knotts vehicle because it can’t translate his physical comedy into animation. It fails as an animated film because the animation is merely functional rather than inspired. It fails as a war film because the stakes feel absurd. It fails as a romance because fish-on-fish love is not the touching interspecies connection the filmmakers seem to think it is.

Most fundamentally, it fails because it never commits to being one kind of movie. It wants to be everything—comedy, drama, war film, romance, fantasy, animation showcase—and ends up being nothing in particular. It’s the cinematic equivalent of a platypus: you can see the individual components that went into its creation, but the final result is just bizarre.

The Bottom Line

The Incredible Mr. Limpet is the kind of movie that seems like it should work on paper. Don Knotts! Animation! World War II! What could go wrong?

Everything, as it turns out.

The film has its defenders, primarily people who encountered it as children and retain nostalgic affection for its weirdness. I can’t fault that nostalgia—we all have movies we loved as kids that probably don’t hold up to adult scrutiny. But I was a kid when I first saw this movie, and even then I recognized it as fundamentally broken.

Revisiting it as an adult only confirmed my childhood assessment. This is a film that mistakes whimsy for imagination, that confuses activity for entertainment, and that fundamentally misunderstands what made Don Knotts funny in the first place. It’s not aggressively terrible—it’s too mild-mannered for that—but it’s a slog, a cinematic experience that feels much longer than its 99-minute runtime suggests.

The Incredible Mr. Limpet isn’t the worst movie I’ve ever seen—we’ve got 35 more entries to go before we hit the absolute bottom of this list—but it’s a movie I have no desire to ever watch again. Once was enough. Twice was research. Three times would be punishment.

Next Week on Movie Monday

Join me next Monday when we continue our descent with number 35 on the list, Not Another Teen Movie. Until then, may your transformations be less fishy and your war efforts more credible.

What are your thoughts on The Incredible Mr. Limpet? Beloved childhood memory or baffling relic? Did anyone else grow up watching this on TBS, or was that torture unique to my region? Share your experiences in the comments below—I’m particularly curious to hear from anyone who actually found the Limpet/Ladyfish romance touching rather than deeply weird.

At first glance I assumed you just didn’t like Don Knotts, but I guess his movies weren’t for everyone. Especially The Incredible Mr. Limpet which I agree is a very strange movie with too many contrasting ideas that don’t go together. I think the Ladyfish romance would’ve only worked if he wasn’t married and had no hope of becoming a human again. Otherwise, it is very weird. As was the World War II angle that made Mr. Limpet the only fish with a confirmed kill count. Part of me wishes they made those remakes, but a comedian’s face superimposed onto a fish body would’ve been nightmarish. I guess we’ll always have Shark Tale for that.

LikeLiked by 1 person