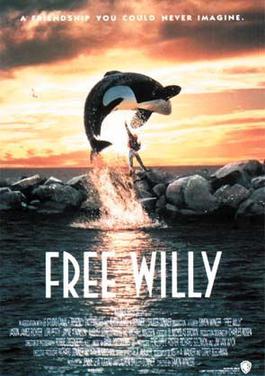

Free Willy

1993

Directed by Simon Wincer

Welcome back to Movie Monday, where we continue our masochistic march through my personal pantheon of cinematic failures. Before we proceed, my standard disclaimer: this list represents nothing more than one man’s opinion, formed by a particular set of experiences and biases that may bear no resemblance to your own. What I consider unwatchable schmaltz might be the film that defined your childhood, the movie you watched every sick day home from school, or the VHS tape you wore out through repeated viewings. Cinema is subjective, and my disdain for these films doesn’t invalidate your nostalgia. Take my criticisms with a grain of salt—or perhaps an entire salt lick, given how many sacred cows I’m about to tip.

This week brings us to number 37: Free Willy, a 1993 film that asked America’s children to believe that a boy’s harmonica playing could forge a mystical bond with a captive orca, and that the solution to animal captivity was… well, we’ll get to that. I need to acknowledge upfront that I’m stepping on approximately 30 million Millennial toes here. For many of you, this film represents a cherished piece of childhood, a movie that made you cry, made you care about marine life, and maybe even inspired you to write letters demanding Keiko’s freedom. I can only apologize so much for what I’m about to say, but know that I understand I’m attacking something beloved. It’s just that being beloved doesn’t make it good.

I was 13 when Free Willy hit theaters, which placed me in that peculiar purgatorial age where I was too old to admit enjoying “kid stuff” but too young to appreciate it ironically. I had already decided I was far too cool for family films—this was the summer I was probably listening to Pearl Jam and pretending to understand what “Jeremy spoke in class today” meant. So yes, I walked into that theater pre-disposed to hate it, though I can’t even remember who dragged me there. Parents? An older cousin? A friend’s parents who hadn’t yet realized I was a cynical little punk? The details are lost to time, but the memory of my disdain remains crystal clear.

The Michael Jackson of It All

Let’s start with the elephant seal in the room: that song. “Will You Be There” by Michael Jackson, which played over the end credits and approximately every ten minutes on every radio station throughout the summer of 1993. If I was going to listen to a ’90s song featuring a gospel choir, it had better be Billy Joel’s “River of Dreams,” not Michael Jackson doing his best Whitney Houston impression while talking about holding and lifting and carrying like he’s running a moving company.

The song itself isn’t terrible—this is Michael Jackson we’re talking about—but its deployment in the film and subsequent marketing represents everything wrong with Free Willy‘s approach to emotion. It doesn’t trust the audience to feel anything without being explicitly told what to feel, when to feel it, and how hard to feel it. The swelling orchestral prelude, the choir, Jackson’s tremulous vocals asking if you’ll be there—it’s emotional manipulation so naked it might as well be wearing a sign that says “CRY NOW.”

And now, despite being decades since I’ve even heard that song, it is currently playing loudly in my mind. I now regret ever considering writing this post.

The E.T. Comparison That Fails

Free Willy desperately wants to be E.T. with a whale. The parallels are obvious: lonely child befriends non-human creature, mean adults want to exploit said creature, child must free creature in climactic scene involving improbable physical feat. But where E.T. succeeded through Spielberg’s masterful direction and a genuine emotional core, Free Willy fails through ham-fisted execution and a fundamental misunderstanding of its own premise.

E.T. was an intelligent, sentient being—essentially a person in an alien body who could communicate, form complex thoughts, and make moral choices. The relationship between Elliott and E.T. was a friendship between equals, despite their different species. Yes, killer whales are incredibly intelligent, but Free Willy asks us to believe that Jesse and Willy share something deeper than trainer and animal, something more akin to a meeting of souls. This might work if the film committed to either making Willy anthropomorphically human-like (à la Disney) or treating him realistically as a wild animal. Instead, it occupies an uncomfortable middle ground where Willy is whatever the plot needs him to be at any given moment.

The Harmonica Problem

The moment Jesse plays his harmonica and Willy responds, the film loses any credibility it might have had. Not because whales can’t respond to music—they can and do—but because the film treats this like some kind of mystical connection rather than simple conditioning. It’s the whale-as-pet problem taken to its logical extreme: this isn’t a story about respecting wild animals, it’s a fantasy about having the world’s largest dog that happens to live in water.

The film wants us to believe that Jesse, through the power of his mediocre harmonica skills and troubled childhood, has formed a unique bond that no one else could achieve. This is narcissism disguised as environmentalism. The message isn’t “whales deserve freedom because they’re sentient beings,” it’s “this whale deserves freedom because a special boy loves him.” It’s the same anthropocentric worldview that led to captivity in the first place, just wrapped in a different package.

Jason James Richter: A Performance for the Ages (The Stone Age)

Watching Jason James Richter in Free Willy is like watching someone learn to act in real-time, except the learning never quite happens. His line delivery has all the nuance of a telegram: I AM SAD. STOP. WHALE IS FRIEND. STOP. ADULTS BAD. STOP.

This isn’t entirely his fault—child actors are only as good as their direction, and director Simon Wincer seems to have directed him with all the subtlety of a marine park announcer. But Richter brings a special quality to the role, a kind of aggressive blandness that makes you long for the emotive range of young Anakin Skywalker. When he’s supposed to be bonding with Willy, he looks constipated. When he’s supposed to be angry at adults, he looks constipated. When he’s triumphant at the end, he looks… relieved? (The constipation metaphor tracks.)

That Richter would go on to play Bastian in The NeverEnding Story III should surprise no one—he had already proven his ability to drain magic from any concept he touched.

The Foster Family Subplot Nobody Asked For

The film dedicates an unconscionable amount of runtime to Jesse’s relationship with his foster parents, played by Michael Madsen and Jayne Atkinson, who deliver performances that suggest they’re in different movies. Madsen appears to think he’s in a gritty indie drama about working-class struggle. Atkinson seems to believe she’s in an after-school special about the power of love. Neither seems aware they’re in a movie about a whale.

The subplot exists solely to give Jesse something to do when he’s not teaching Willy to jump through hoops, but it’s so perfunctory it might as well have been generated by an early-’90s screenplay software program. Foster parents try to connect with troubled youth: Check. Youth resists but slowly warms up: Check. Crisis brings them together as real family: Check. It’s painting by numbers, except someone forgot to include the paint.

The Villains Who Weren’t Even Trying

Michael Ironside plays Dial, the park owner who wants to kill Willy for insurance money, with all the subtlety of a Saturday morning cartoon villain. He might as well be twirling a mustache and tying orcas to railroad tracks. The film’s environmental message would carry more weight if the antagonist had any motivation beyond “I like money.” Even Captain Planet had more nuanced villains.

The frustrating thing is that there’s a genuinely complex story to be told about the economics of marine parks, the entertainment industry’s relationship with animal welfare, and the competing interests of conservation and capitalism. But Free Willy isn’t interested in complexity. It’s interested in clear heroes and villains, simple problems and magical solutions.

That Jump Scene

And now we arrive at it: the scene that launched a thousand posters and traumatized a generation of marine biologists. The climactic jump where Willy leaps over Jesse and the breakwater to freedom.

Let’s be clear about what the film is asking us to accept: a whale that has been in captivity for years, is malnourished and suffering from skin conditions, and has just been transported in a truck (a famously stress-free experience for marine mammals), summons the strength to make a jump that would challenge a healthy whale in peak condition. He does this because a 12-year-old boy made the “jump” hand signal.

The scene is shot in slow motion, naturally, with Michael Jackson’s voice soaring as high as Willy himself. It’s meant to be triumphant, transcendent, a moment of pure cinema magic. Instead, it’s ridiculous on a level that makes the ending of The NeverEnding Story (where a kid rides a luck dragon through modern-day cities) look like cinéma vérité. The animatronic Willy looks about as convincing as a parade float, and the green screen work has that special early-’90s quality where you can practically see the seams.

The Keiko Problem

We need to talk about Keiko.

The real orca who played Willy became, through no fault of his own, the center of one of the most well-intentioned and ultimately tragic environmental campaigns of the 1990s. The “Free Keiko” movement, sparked by the film’s success, raised $20 million to rehabilitate and eventually release him into the wild. It was a beautiful idea executed with horrible results.

Keiko, captured near Iceland at age two and kept in captivity for over 20 years, was a terrible candidate for release. He had no pod, no hunting skills, and a deep dependence on humans for food and companionship. After years of preparation and millions of dollars, he was released in 2002 only to seek out human contact in Norwegian fjords, allowing children to ride on his back like some kind of massive, tragic pool toy. He died in 2003, having never successfully integrated with wild orcas.

The scientists involved later admitted what should have been obvious from the start: you can’t simply release an institutionalized animal and expect a Disney ending. But Free Willy had convinced millions of people that freedom was just a matter of will (no pun intended) and love. The film’s legacy isn’t just bad cinema—it’s bad conservation policy driven by emotional manipulation rather than science.

The Environmental Message That Wasn’t

Free Willy poses as an environmental film, but its message is fundamentally anti-environmental. It suggests that individual action driven by emotion is superior to systematic change based on science. It implies that animal captivity is wrong not because it violates the autonomy of sentient beings, but because it makes one special boy sad. It proposes solutions—literally jumping over the problem—rather than addressing root causes.

Compare this to something like Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home, which also features whales and time travel and is completely ridiculous but at least acknowledges that saving whales requires more than good intentions. Or even Star Trek‘s slightly heavy-handed but sincere environmental messaging. Free Willy isn’t interested in the environment; it’s interested in making children cry and parents open wallets.

Why Free Willy Earns Its Spot at Number 37

Free Willy sits at number 37 not because it’s incompetently made—the technical aspects are fine, if uninspired—but because it represents a particular kind of cynical filmmaking that disguises itself as heartfelt. It’s a corporate product pretending to be countercultural, a film that exploits the very thing it claims to protect.

This is a movie that took a real orca suffering in a Mexican theme park and turned him into a prop for a story about a white kid’s feelings. It sparked a movement that spent $20 million on a doomed release project that could have funded actual conservation efforts. It convinced a generation that complex environmental problems have simple, emotional solutions. It’s not just bad entertainment; it’s actively harmful messaging dressed up as family fun.

The Bottom Line

Free Willy is the cinematic equivalent of a marine park itself: a sanitized, commercialized version of something that should be wild and free. It takes the genuine majesty of orcas and reduces them to performers in a drama about human emotional needs. It’s a film that mistakes sentimentality for sentiment, manipulation for emotion, and jumping over problems for solving them.

For those who cherish their memories of crying over this film, I can only say that I understand the power of childhood nostalgia. But sometimes the things we loved as children deserve to be re-examined with adult eyes. And with adult eyes, Free Willy looks less like a triumph of the human-animal bond and more like a cautionary tale about what happens when Hollywood tries to solve real problems with fake whales and real sentiment.

Next week on Movie Monday, we’ll take a break from our descent through the depths of cinematic disappointment with the next animated Disney film on the list: The Aristocats. Until then, remember: the only thing that should be freed is your DVD shelf from the burden of carrying this movie.

What are your thoughts on Free Willy? Did it inspire your childhood environmental activism, or did you, like me, see through the manipulation even as a kid? And can anyone explain why that Michael Jackson song was everywhere that summer? Share your experiences in the comments below—I’m particularly curious to hear from anyone who participated in the “Free Keiko” campaign and whether you feel differently about it now.

Although I’m a Millennial, I actually didn’t grow up watching Free Willy. So I’m not sentimental about. But that doesn’t mean I didn’t enjoy it and cry when I saw it for the first time as an adult. I hear what you’re saying about environmental messaging and Keiko, but I think Free Willy is relatively harmless. Have you seen any of the sequels?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nah… I skipped out on the rest of this franchise.

LikeLiked by 1 person