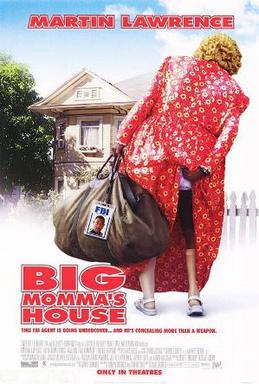

Big Momma’s House

2000

Directed by Raja Gosnell

Welcome back to Movie Monday, where we continue our descent through my personal catalog of cinematic disappointments. Before we dive in, let me offer my standard disclaimer: this list represents my personal opinion and nothing more. What I consider unwatchable dreck might be your favorite comfort movie, the film you quote with friends, or the comedy that never fails to lift your spirits. Cinema is subjective, and my distaste for these films doesn’t invalidate your enjoyment of them. Take my criticisms with a grain of salt—or better yet, a whole shaker.

This week brings us to number 39: Big Momma’s House, a 2000 comedy that asks the eternal question: what if we took the cross-dressing comedy formula that had already been perfected and exhausted by better films, added a healthy dose of toilet humor, and stripped away any semblance of heart or purpose? The answer, unfortunately, is 99 minutes of Martin Lawrence in a fat suit, proving that sometimes Hollywood’s recycling program extends to jokes that weren’t particularly funny the first time around.

I first encountered Big Momma’s House on video during college, at that peculiar age when you’re old enough to recognize lazy filmmaking but young enough to still hope for pleasant surprises from rental store shelves. Even with my standards temporarily lowered by dorm life and late-night study sessions, the film left me distinctly unimpressed. Sure, I probably laughed at a moment or two—comedy shotgun blasts occasionally hit their target through sheer volume of ammunition—but the overall experience felt like watching someone perform CPR on a corpse that had been dead since Tootsie walked out of theaters.

The Cross-Dressing Comedy Exhaustion

By the year 2000, the cross-dressing comedy had already lived through multiple lifecycles. From Some Like It Hot‘s genre-defining brilliance through Tootsie‘s thoughtful exploration of gender dynamics, to Mrs. Doubtfire‘s heartfelt family drama wrapped in prosthetic breasts, the format had been mined for every conceivable nugget of comedy gold. Even The Nutty Professor had managed to find fresh angles by combining the formula with Jekyll and Hyde dynamics and genuine romantic pathos.

Into this thoroughly excavated comedic landscape stumbled Big Momma’s House, arriving like a prospector to a ghost town, metal detector in hand, convinced that everyone else must have missed something.

The film’s fundamental miscalculation begins with its basic premise: FBI agent Malcolm Turner goes undercover as an elderly Southern grandmother to catch an escaped convict. Where Mrs. Doubtfire used the disguise to explore themes of fatherhood and divorce, and Tootsie examined workplace sexism and artistic integrity, Big Momma’s House uses its central conceit primarily as an excuse for fat jokes and toilet humor. The difference between homage and grave-robbing has never been more apparent.

The Martin Lawrence Problem

To understand why Big Momma’s House fails so spectacularly, we need to examine the particular comedy stylings of Martin Lawrence circa 2000. This was Lawrence at an interesting crossroads in his career—successful enough to headline major studio comedies, but never quite achieving the crossover appeal of contemporaries like Eddie Murphy or Will Smith. His sitcom Martin had ended three years earlier amid controversy and lawsuits, and his film career existed in a strange limbo between action comedy (Bad Boys) and increasingly desperate attempts at family-friendly fare.

Lawrence possessed undeniable energy and commitment to physical comedy, but his particular brand of humor always felt more abrasive than inviting. Where Robin Williams brought warmth to Mrs. Doubtfire and Dustin Hoffman brought vulnerability to Tootsie, Lawrence brings a kind of manic aggression that transforms what should be gentle comedy into something more akin to an assault. His Big Momma doesn’t feel like a fully realized character so much as a collection of stereotypes delivered at maximum volume.

The year 2000 found Lawrence in a peculiar position. His personal struggles had been well-documented—a 1996 incident involving him screaming in traffic while wielding a firearm, a 1999 coma following a heat stroke while exercising in heavy clothing—suggesting someone battling demons that comedy couldn’t quite exorcise. Big Momma’s House arrived as an attempt to rehabilitate his image through broadly acceptable family comedy, but the strain shows in every frame. This is comedy performed through gritted teeth, laughter extracted rather than inspired.

The Toilet Humor Nadir

If there’s a single scene that encapsulates everything wrong with Big Momma’s House, it’s the now-infamous bathroom sequence where Malcolm, hiding behind a shower curtain, is forced to witness Big Momma’s extended bathroom activities following a meal of stewed prunes. The scene plays out with the kind of prolonged commitment to scatological humor that suggests screenwriters Darryl Quarles and Don Rhymer mistook audience discomfort for comedy gold.

This sequence reveals the film’s fundamental misunderstanding of its own genre. Cross-dressing comedies work when the protagonist’s disguise forces them to navigate unfamiliar social situations, creating comedy through character growth and cultural observation. Instead, Big Momma’s House trades in the laziest form of physical comedy, assuming that bodily functions become inherently funny when performed by elderly Black women. It’s not just that the joke isn’t funny—it’s that the joke reveals an ugly contempt for the very character the film asks us to care about.

The toilet scene problem extends throughout the film’s approach to humor. Rather than mining comedy from Malcolm learning to navigate the world as Big Momma, the film repeatedly falls back on the most obvious physical gags: Big Momma plays basketball! Big Momma does karate! Big Momma delivers a baby! Each setup plays out with mechanical precision and minimal imagination, as if the writers brainstormed “things that would be funny for a fat old lady to do” without considering whether any of these scenarios actually generated humor beyond the initial incongruity.

The Prosthetic Performance Problem

Greg Cannom’s makeup work on Big Momma’s House deserves recognition for technical achievement—the same artist who transformed Robin Williams in Mrs. Doubtfire and Bicentennial Man certainly knew his craft. The prosthetics are convincing enough, the fat suit moves naturally, and from a purely technical standpoint, the transformation is impressive. But technical proficiency can’t overcome fundamental performance problems, and Lawrence’s interpretation of Big Momma feels less like character work and more like an extended impression performed at gunpoint.

The problem isn’t just that Lawrence plays Big Momma as a collection of stereotypes—it’s that he plays her without affection or understanding. Where Williams’ Mrs. Doubtfire felt like a fully realized character who happened to be a disguise, Big Momma never transcends caricature. She’s all surface mannerisms and vocal affectations, a puppet made of latex and tired jokes about Southern Black grandmothers who say things like “Oh, Lord!” and hit people with their purses.

The Wasted Supporting Cast

Perhaps the greatest crime Big Momma’s House commits is wasting a genuinely talented supporting cast on material that gives them nothing to do but react to Lawrence’s antics. Nia Long, who had proven her dramatic chops in films like Love Jones and The Best Man, is reduced to playing the straight woman in a romance that develops with all the chemistry of mixing oil and water. Her character, Sherry, exists primarily to be deceived and then forgiven, her entire arc determined by the needs of Malcolm’s deception rather than any internal logic or character development.

Paul Giamatti, still a few years away from Sideways and genuine recognition, brings his trademark nervous energy to the thankless role of Malcolm’s partner, but the script gives him nothing to do but worry and occasionally provide exposition. Terrence Howard appears as the villain, displaying hints of the intensity that would later earn him an Oscar nomination for Hustle & Flow, but he’s playing a character so thinly written he might as well be named “Generic Bad Guy #1.”

The romantic subplot between Malcolm and Sherry deserves special mention for its complete failure to generate any emotional investment. The film asks us to believe that Sherry falls for Malcolm while he’s pretending to be her grandmother, which raises uncomfortable questions the movie has no interest in exploring. When the deception is revealed, her sense of betrayal lasts approximately thirty seconds of screen time before true love conquers all in a church scene so manipulatively saccharine it makes Hallmark movies look like gritty realism.

The Comedy Landscape of 2000

To understand how Big Momma’s House found an audience despite its creative bankruptcy, we need to consider the comedy landscape of 2000. This was the height of the gross-out comedy era, where the Farrelly Brothers had made bodily fluids bankable and American Pie had proven that audiences would embrace increasingly crude humor. The comedy bar hadn’t been lowered so much as buried underground, creating an environment where any film that could string together enough isolated funny moments could find box office success regardless of overall quality.

Big Momma’s House arrived as a sanitized version of this trend, gross enough to appeal to audiences conditioned by There’s Something About Mary but safe enough for date nights and eventual cable television rotation. It occupied a cynical sweet spot: edgy enough for teenagers, tame enough for grandparents, and requiring absolutely nothing from anyone in terms of thought or emotional engagement.

The Inexplicable Box Office Success

Here’s where the story of Big Momma’s House becomes truly depressing: it was a massive hit. The film grossed $174 million worldwide against a $30 million budget, proving once again that quality and profitability exist in entirely separate universes. Audiences gave it an “A” CinemaScore, suggesting that paying viewers found exactly what they were looking for, which raises uncomfortable questions about what exactly that was.

The film’s success becomes even more baffling when you consider the critical reception. With a 30% Rotten Tomatoes score and reviews that ranged from disappointed to openly hostile, critics saw through the film’s lazy construction immediately. Roger Ebert, always more generous than most, admitted to laughing while still recognizing the film’s essential tastelessness. The disconnect between critical assessment and audience enthusiasm reveals something depressing about lowest-common-denominator entertainment: sometimes people just want noise and movement that vaguely resembles comedy, actual humor optional.

The Sequel Industrial Complex

The most damning thing about Big Momma’s House‘s success isn’t that it made money—plenty of bad movies make money—it’s that it spawned not one but two sequels. Big Momma’s House 2 arrived in 2006, followed by Big Mommas: Like Father, Like Son in 2011, each iteration moving further from the already questionable original concept. I’ll admit to never watching either sequel, a decision I’ve never questioned or regretted. When the first film leaves you cold, subjecting yourself to the follow-ups feels less like entertainment and more like voluntary punishment.

The existence of these sequels reveals Hollywood’s most cynical tendency: the willingness to transform any profitable property into a franchise, regardless of whether there’s any creative reason to do so. The cross-dressing comedy, already a tired format by 2000, became a trilogy stretched across a decade, each installment presumably finding diminishing returns both financially and creatively. It’s the cinematic equivalent of beating a dead horse, then beating the spot where the horse used to be, then franchising the beating process.

The Cultural Damage Assessment

Beyond its failures as entertainment, Big Momma’s House represents something more insidious: the commodification and mockery of Black grandmotherhood for mainstream consumption. The film asks audiences to laugh at Big Momma rather than with her, mining humor from stereotypes about elderly Black women that feel uncomfortable at best and deliberately demeaning at worst. The fact that it’s a Black actor performing these stereotypes doesn’t make them less problematic—if anything, it makes the entire enterprise feel more cynical.

Film scholars have noted how movies like Big Momma’s House perpetuate damaging representations while hiding behind the shield of comedy. The fat suit becomes a form of cultural drag that allows audiences to laugh at bodies and identities they might otherwise have to respect. It’s minstrelsy with a bigger budget and better prosthetics, using technological advancement to perfect the art of punching down.

Why Big Momma’s House Earns Its Spot at Number 39

Big Momma’s House sits at number 39 on my worst movies list not because it’s incompetently made—the technical aspects are professional enough—but because it represents a perfect storm of creative laziness, cultural insensitivity, and cynical commercialism. This is a film that takes a worn-out concept, strips it of any remaining dignity or purpose, adds toilet humor and stereotypes, and packages the result as family entertainment.

The film fails on multiple levels simultaneously. As a comedy, it mistakes volume for humor and stereotypes for character. As an action film, it delivers perfunctory set pieces that feel obligatory rather than exciting. As a romance, it presents a relationship built on deception and resolved through manipulation. As a star vehicle for Martin Lawrence, it highlights his limitations rather than his strengths. There’s no single aspect of Big Momma’s House that succeeds on its own terms.

Most frustrating is the film’s complete lack of ambition. While Mrs. Doubtfire used its premise to explore divorce and fatherhood, and Tootsie examined gender dynamics and artistic integrity, Big Momma’s House has absolutely nothing on its mind beyond reaching the next pratfall. It’s comedy as product rather than art, assembled from focus group feedback and demographic targeting rather than any genuine creative impulse.

The Bottom Line

Big Momma’s House stands as a monument to everything wrong with Hollywood’s approach to comedy in the early 2000s: the assumption that audiences will accept lazy stereotypes as character development, that toilet humor can substitute for wit, and that any successful film deserves to become a franchise. It’s a film that manages to waste talent, squander potential, and insult its audience’s intelligence all while maintaining a cheerful conviction that it’s providing wholesome family entertainment.

The film’s success—both financial and in spawning sequels—represents a kind of cultural surrender, an admission that we’ll accept entertainment that doesn’t even pretend to try. While there are certainly worse films from a technical standpoint, few combine commercial calculation with creative bankruptcy quite as nakedly as Big Momma’s House.

For those who found genuine entertainment in watching Martin Lawrence in a fat suit navigating tired comedy scenarios, I can only offer my bewilderment. The film exists as proof that sometimes the marketplace rewards mediocrity, and that Hollywood will always choose the safe, stereotypical, and stupid over anything that might require actual thought or creativity.

Next week on Movie Monday, we’ll continue our descent through cinematic disappointments with another film that proves sometimes Hollywood’s recycling program produces toxic waste rather than renewed resources. That’s right, we’re talking about Problem Child 2. Until then, remember: not every successful comedian needs a fat suit vehicle, and sometimes the best disguise a bad movie can wear is box office success.

What are your thoughts on Big Momma’s House? Did you find humor in Lawrence’s prosthetic performance that eluded me, or do you agree that this represents the nadir of both cross-dressing comedies and Lawrence’s film career? Share your experiences in the comments below—I’m particularly curious to hear from anyone brave enough to have watched the sequels and lived to tell the tale.

I agree that Big Momma’s House is a bad movie with tired toilet humor and stereotypical jokes. That being said, the honor of worst “old black woman cross-dressing comedy” probably goes to any of the Madea movies. Big Momma’s House was something I knew I had to see at some point since I was part of the generation that made it popular. The sequels are definitely worse. Though Big Momma’s House 2 isn’t quite as unwatchable as the awful Like Father, Like Son that puts the grown up son in a dress as well.

LikeLiked by 1 person