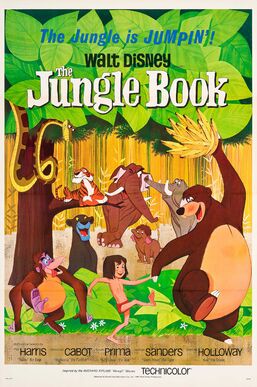

The Jungle Book

1967

Directed by Wolfgang Reitherman

Welcome back to Movie Monday, dear readers! Since this is the first Monday of the month, we’re taking our customary break from my ongoing exploration of cinema’s most spectacular failures to enjoy a palate cleanser. Today, we’re venturing into the jungles of India with Disney’s 1967 animated classic The Jungle Book—a film that holds the bittersweet distinction of being the last animated feature Walt Disney personally touched before his death in December 1966.

I’ll confess something upfront: The Jungle Book was never a particular favorite of mine growing up. While songs like “The Bare Necessities” and “I Wanna Be Like You” are undeniably classics—the kind of earworms that burrow into your brain and set up permanent residence—the film itself always felt somewhat disconnected to me, a collection of memorable moments rather than a cohesive whole. But revisiting it now, with the context of its production history and its place as Walt Disney’s unexpected farewell, I find myself appreciating it in ways my younger self never could.

The Weight of an Unintended Goodbye

The production of The Jungle Book carries a melancholy that colors every frame, though you’d never know it from the film’s bouncing, jazz-infused energy. Walt Disney died on December 15, 1966, ten months before the film’s October 1967 premiere. Unlike The Sword in the Stone, which Disney saw through to completion, The Jungle Book exists in a strange twilight—the last film he actively shaped but never saw finished, making it less a deliberate final statement than an interrupted conversation.

The timing couldn’t have been more poignant or ironic. After the critical reception of The Sword in the Stone, Walt decided to become more hands-on with The Jungle Book than he had been with the previous two films. He attended story meetings, acted out character roles, and made decisive creative choices that would fundamentally reshape the source material. In essence, Walt Disney spent his final years teaching his animation team one last masterclass in how to craft family entertainment—though neither he nor they knew it would be his last.

Bill Peet’s Dramatic Exit and Disney’s Creative Coup

The story behind The Jungle Book‘s story is almost as dramatic as anything on screen. Bill Peet, who had single-handedly adapted 101 Dalmatians and The Sword in the Stone, spent over a year crafting a treatment that closely followed Rudyard Kipling’s dark, episodic source material. His version would have been a more faithful, serious adaptation—complete with a climax featuring Mowgli using a hunter’s rifle to kill Shere Khan after the tiger had murdered the treasure-hunting Buldeo.

Walt Disney took one look at Peet’s treatment and essentially said, “This is too dark, too depressing, and too damn literary.” The resulting confrontation became the stuff of animation legend. On January 29, 1964, after a particularly heated argument (during which Disney reportedly told Peet he should watch Mary Poppins for “real entertainment”), Bill Peet walked out of Disney Studios and never came back.

Enter Larry Clemmons, Disney’s new writer, whom Walt handed a copy of Kipling’s book with the immortal instruction: “The first thing I want you to do is not to read it.” This single directive encapsulates Disney’s entire philosophy for the film—forget the source material’s colonial complexities and episodic structure, focus on character, comedy, and heart. It was a creative decision that would have made purists apoplectic but resulted in one of Disney’s most enduring crowd-pleasers.

The Celebrity Voice Revolution

One of Walt Disney’s smartest decisions for The Jungle Book was breaking with tradition and casting celebrity voices rather than anonymous voice actors. This wasn’t just stunt casting—Disney instructed his animators to study the actors’ mannerisms and personalities, essentially building the characters around their voices rather than the reverse.

Phil Harris as Baloo is the film’s masterstroke. Disney initially approached Harris at a benefit in Palm Springs, and the animation staff was skeptical—how could this Las Vegas comedian embody Kipling’s serious, responsible bear mentor? The answer was simple: he wouldn’t. Disney told Harris to “not be a bear, but be Phil Harris,” and the result transformed Baloo from Mowgli’s stern teacher into the jungle’s most loveable slacker. Harris improvised many of his lines, bringing a jazzy, improvisational energy that turned “The Bare Necessities” into not just a song but a philosophy of life.

The King Louie casting situation reveals both the era’s complications and Disney’s attempts to navigate them. Louis Armstrong was initially considered for the role, which would have been inspired casting—who better than Satchmo to lead a swinging jungle jazz number? But someone in a story meeting pointed out the awful optics of having a Black performer voice an ape character, and the idea was quickly shelved. Instead, they cast Louis Prima, the Italian-American bandleader whose manic energy and distinctive voice created a character that’s simultaneously problematic and undeniably entertaining.

George Sanders as Shere Khan brought something unexpected to Disney villainy—sophisticated menace delivered with drawing-room politeness. Sanders’ cultured, almost bored delivery makes Shere Khan more terrifying than any amount of snarling could achieve. When he tells Kaa, “I can’t be bothered with that, I have no time for that nonsense,” while searching for a boy to murder, the casual dismissiveness is chilling.

The Sherman Brothers Find Their Groove

The Jungle Book marked the Sherman Brothers’ first complete Disney animated feature score (Terry Gilkyson’s “The Bare Necessities” being the lone survivor from an earlier, darker version), and they approached it with a clever conceit: what if the jungle swung—literally? They reimagined Kipling’s India as a jazz-age wonderland where bears scat, orangutans swing (musically and physically), and even elephants march to a military beat that wouldn’t be out of place in a British music hall.

“I Wanna Be Like You” is a masterpiece of musical storytelling that manages to be simultaneously catchy, character-revealing, and deeply uncomfortable when viewed through a contemporary lens. The Sherman Brothers built the entire number around the concept of “swing”—apes swing, jazz swings, so King Louie’s big number had to swing. They even brought Louis Prima to a soundstage in Las Vegas to watch him perform with his band, incorporating his physicality into the animation.

But it’s “The Bare Necessities” that became the film’s signature song, earning an Oscar nomination and embodying the film’s entire philosophical shift from Kipling’s source material. Where Kipling used the jungle as a metaphor for the dangers of the uncivilized world, Disney’s jungle became a place where you could literally float down a river, eat bananas, and scratch your back against a tree while dispensing life advice. It’s American optimism colonizing British colonial literature, and somehow it works.

Animation Economics and Artistic Compromise

By 1967, Disney animation was at a crossroads. The xerography process that had saved money on 101 Dalmatians and The Sword in the Stone was now the standard, but at a cost—the lush, painterly backgrounds of Sleeping Beauty were gone, replaced by a scratchier, more economical style. The jungle of The Jungle Book feels less like an actual place than a theatrical backdrop, which oddly works for a film that’s essentially a series of vaudeville acts connected by a very loose plot.

Wolfgang Reitherman, directing his first solo Disney feature, made a controversial choice that would define Disney’s approach for the next decade: recycling animation. Entire sequences from previous films were traced and reused—the wolf cubs are redrawn dalmatian puppies, Mowgli’s movements occasionally mirror Arthur from The Sword in the Stone, and dance sequences that would later be recycled again in Robin Hood. From a business perspective, it was genius. From an artistic perspective, it was… well, let’s just say you can’t unsee it once you know it’s there.

Yet despite these economical constraints, The Jungle Book contains moments of genuine animation brilliance. The elephant patrol sequence, with its precise military timing, shows Disney’s animators at their comedic best. The hypnosis sequences with Kaa demonstrate how much character can be conveyed through eye animation alone. And the final confrontation between Baloo and Shere Khan, while brief, carries real dramatic weight through its staging and character animation.

The Problem of Progress

Let’s address the elephant (patrol) in the room: The Jungle Book has not aged gracefully in all respects. Disney+ now plays the film with a content warning about “outdated cultural depictions,” and it’s not hard to see why. King Louie and his monkey kingdom, despite being voiced by an Italian-American, play into uncomfortable stereotypes with their jazz-age styling and desire to become “human.” The very premise—that Mowgli must leave the jungle for “civilization”—carries colonial implications that Kipling might have intended but feel problematic today.

The film’s treatment of its female characters is… well, there’s basically only one, and she exists solely to lure Mowgli to the man-village with her water jug and batting eyelashes. The girl (she doesn’t even get a name in the film) represents civilization as domestic attraction, using feminine wiles to accomplish what Bagheera’s logic and Baloo’s pleading couldn’t. It’s a narrative choice that reduces both growing up and cultural identity to a pretty girl with a water jug.

Yet there’s something to be said for how the film acknowledges its own problems, even if unconsciously. King Louie’s villain song is literally about wanting to appropriate human culture (“I wanna be like you”). The film’s conclusion, with Mowgli choosing the human village, can be read as either affirming the necessity of cultural assimilation or suggesting that fighting against one’s nature (even a loving, accepting found family) leads to inevitable conformity.

Walt’s Final Innovation

What makes The Jungle Book fascinating as Walt Disney’s final film is how it represents both his greatest strengths and his creative limitations. His insistence on lightening Kipling’s dark source material shows his unerring instinct for what family audiences wanted, but also his reluctance to engage with challenging themes. His embrace of celebrity voice casting and contemporary music styles showed his innovative spirit, while the recycled animation revealed the financial pressures he was under.

The film’s episodic structure—essentially a road movie where Mowgli bounces from one encounter to another—feels both loose and purposeful. Each sequence works as its own short film: Mowgli and the elephants, Mowgli and the monkeys, Mowgli and the vultures. It’s variety show entertainment masquerading as a narrative feature, held together by charm rather than plot logic.

But perhaps that’s exactly what Disney intended. In his last creative act, he wasn’t trying to make Pinocchio or Bambi. He was making entertainment—pure, simple, and joyful. The film’s massive success ($23.8 million worldwide, eventually becoming Germany’s highest-grossing film by admissions) proved he still understood his audience, even if he wouldn’t live to see their response.

The Remake That Worked

Here’s something I never thought I’d write: Jon Favreau’s 2016 live-action/CGI remake of The Jungle Book is better than the original. This is the only time—let me repeat, the ONLY time—I’ve preferred a Disney live-action remake to its animated predecessor. While every other remake from Beauty and the Beast to The Little Mermaid has felt like a soulless cash grab, Favreau’s Jungle Book actually understood what made the original work while fixing its narrative problems.

The remake gives the episodic encounters actual purpose, makes the wolf pack feel like a real family Mowgli is leaving behind, and gives even King Louie (voiced by Christopher Walken doing his best apocalyptic mob boss) genuine menace. It takes the original’s best elements—the songs, the character dynamics, the essential warmth—while adding the narrative coherence the 1967 version lacks.

The Bare Necessities of Legacy

Watching The Jungle Book today is a bittersweet experience. It’s impossible not to see it as Walt Disney’s goodbye, even though he never intended it as such. The film’s philosophy—essentially Baloo’s carefree “Bare Necessities” approach to life—seems almost rebellious coming from a man who built an empire on careful planning and obsessive attention to detail.

Yet maybe that’s the most honest thing about it. At the end of his life, perhaps Walt Disney wanted to remind us that sometimes the simple things—a catchy song, a silly dance, a bear scratching his back against a tree—are what really matter. The film doesn’t try to be profound or revolutionary. It just wants to entertain, to make children laugh and adults tap their feet.

The film’s flaws are obvious: its narrative looseness, its problematic elements, its corner-cutting animation. But its virtues are equally clear: memorable characters, infectious music, and a warmth that transcends its technical limitations. It’s comfort food cinema, familiar and satisfying even when you know it’s not particularly nutritious.

The Jungle Book succeeded in ways Walt Disney probably didn’t anticipate. It became a template for a new kind of Disney film—celebrity-voiced, contemporary-minded, more interested in entertainment than artistry. Whether that’s a legacy to celebrate or mourn depends on your perspective. But there’s no denying that when Baloo and Mowgli float down that river, singing about the bare necessities, something feels complete, even if the man who started it all wasn’t there to see it end.

What are your memories of The Jungle Book? Did you find yourself humming “The Bare Necessities” for days afterward, or did the film’s episodic nature leave you cold? And what do you make of it as Walt Disney’s unintended farewell to animation? Share your thoughts in the comments below—I’d love to hear how this jazzy jungle adventure fits into your Disney canon! Next Monday, we return to our regularly scheduled programming of cinematic disasters with a look at Big Momma’s House. Until then, look for the bare necessities, and remember—sometimes they come looking for you.

The Jungle Book is my #4 favorite Walt Disney animated movie of all time. Making it my highest rated Disney movie not in the Disney Renaissance. Needless to say it’s one of my all time favorites ever since I was a kid. The songs are close to my heart and I love that it’s one of the last movies Walt Disney will be remembered for. I don’t think it’s dated like other Disney movies and the reused animation never bothered me. It all came together with the bare necessities. As for the remake, I think it’s equally as good, but I could never say that it’s better.

LikeLiked by 1 person