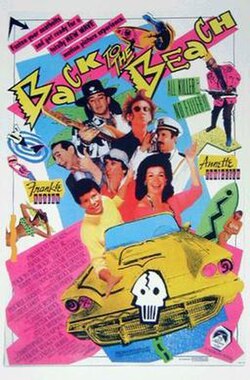

Back to the Beach

1987

Directed by Lyndall Hobbs

Welcome back to Movie Monday, where we continue our methodical journey through my personal countdown of the 100 worst movies I’ve ever subjected myself to. This week brings us to number 40: Back to the Beach, a 1987 comedy that represents Hollywood’s eternal struggle to recapture lightning in a bottle by dusting off beloved properties and hoping nostalgia will do the heavy lifting. It’s a film that asks the eternal question: what happens when you take iconic characters from the 1960s beach party era and transplant them into Reagan-era suburbia? The answer, unfortunately, is 92 minutes of aggressively wholesome comedy that mistakes recognition for humor and celebrity cameos for actual entertainment value.

I first encountered Back to the Beach as a kid, part of that endless cycle of weekend afternoon movies that filled television programming in the pre-streaming era. Even at an age when my comedy standards were calibrated to appreciate Ernest Goes to Camp, something about this particular nostalgia trip felt forced and hollow. The jokes landed with the comedic impact of beach balls hitting sand, and I found myself wondering why all the adults in the movie seemed to think surfing terminology from twenty years ago was inherently hilarious. It was my first real lesson in how desperation can masquerade as whimsy when Hollywood gets nostalgic.

The Beach Party Archaeology Project

Back to the Beach arrives as both sequel and parody to the original American International Pictures beach party films that dominated teenage entertainment in the mid-1960s. Those original movies, starring Frankie Avalon and Annette Funicello, were themselves products of their time—innocent, formulaic, and designed to give parents something they could tolerate while keeping teenagers happy with surf music and minimal clothing. They were cultural artifacts of an America that believed youth culture could be safely contained within the bounds of clean fun and romantic complications that never progressed beyond hand-holding.

By 1987, those films had achieved a kind of camp classic status, remembered fondly by baby boomers who had moved on to mortgages and middle management. The cultural landscape was ripe for nostalgia mining—Grease had proven that audiences would embrace musical comedy callbacks to simpler times, and the 1980s were in the midst of a broader cultural obsession with recycling and repackaging the recent past. Into this environment stepped Back to the Beach, promising to reunite the original stars in a contemporary setting that would acknowledge the passage of time while recapturing the magic of their youth.

The premise had genuine potential. Take beloved characters, age them realistically, and explore what happens when the carefree beach bums of yesterday become the suburban parents of today. It’s a concept that could have supported genuine insight about aging, changing values, and the gap between generational expectations. Instead, the film treats this setup as an excuse for an extended series of “remember when” gags and celebrity cameo appearances.

When Nostalgia Becomes a Substitute for Storytelling

The fundamental problem with Back to the Beach isn’t its desire to revisit beloved characters—it’s the film’s complete inability to find anything meaningful to do with them once they arrive in the contemporary world. Frankie and Annette have become exactly what you’d expect: he’s a stressed car salesman in Ohio, she’s a housewife battling suburban ennui through retail therapy. Their teenage children are rebelling against their square parents, setting up generational conflict that the film resolves through the magical healing power of surfing and song.

This setup contains all the ingredients for either sharp social satire or heartfelt family comedy. Unfortunately, director Lyndall Hobbs and her team of seventeen (yes, seventeen) credited writers seem to have confused concept with execution. The film knows exactly what story it wants to tell but has no idea how to tell it with any creativity or insight. Instead of exploring the genuine comedy inherent in former beach rebels becoming suburban conformists, the film settles for surface-level jokes about hair loss, weight gain, and parental embarrassment.

The script’s approach to humor relies heavily on recognition rather than actual wit. Characters make references to surf culture, past movies, and 1960s slang with the expectation that familiarity will generate laughs. It’s comedy by checklist—include the surf talk, reference the old movies, bring back the music, and assume the audience will fill in the emotional blanks through their own nostalgia. This approach might work for viewers with deep personal investment in the original films, but it leaves everyone else watching a series of inside jokes told by people who seem more amused by their own references than concerned with entertaining their audience.

The Cameo Parade Problem

Perhaps no element of Back to the Beach better illustrates its fundamental confusion about entertainment value than its approach to celebrity cameos. The film features appearances by Don Adams, Bob Denver, Jerry Mathers, Tony Dow, Barbara Billingsley, and Pee-wee Herman, among others. These aren’t organic story appearances but rather a parade of “hey, it’s that guy” moments designed to trigger recognition and applause from viewers who remember these performers from their various television shows.

The problem with this approach is that cameos only work when they serve the story or provide genuine surprise. When they become the primary source of entertainment, they reveal a fundamental lack of confidence in the material itself. Back to the Beach seems to believe that putting Pee-wee Herman on a beach singing “Surfin’ Bird” is inherently funny, regardless of context or execution. The result feels less like comedy and more like a variety show that’s forgotten to include actual variety.

The musical performances suffer from similar issues. Dick Dale and Stevie Ray Vaughan deliver competent versions of surf classics, but their appearances feel like contractual obligations rather than organic story elements. The film includes these musical interludes because beach party movies are supposed to have musical interludes, not because they advance the plot or develop characters in meaningful ways.

Performance and Direction Challenges

Frankie Avalon and Annette Funicello deserve credit for committing fully to their return to characters that made them famous. Both actors approach their roles with genuine affection and professionalism, clearly understanding that they’re participating in something designed to honor their legacy rather than extend it in new directions. Avalon, in particular, demonstrates game enthusiasm for self-deprecating humor about his character’s middle-aged struggles, while Funicello brings warmth to a role that could easily have become a collection of suburban mother stereotypes.

The supporting cast varies wildly in effectiveness. Lori Loughlin as the daughter provides capable straight-woman support, while the various beach punk antagonists feel like refugees from a different movie entirely. The generational conflict between old-school surfers and new wave beach culture could have provided genuine dramatic tension, but the film never commits strongly enough to either side to make their eventual reconciliation feel earned.

Lyndall Hobbs, directing her first feature film after a career in music videos, brings visual competence to the proceedings without developing a clear comedic voice. The film looks professional and maintains adequate pacing, but never develops the rhythmic timing that effective comedy requires. Scenes play out with mechanical precision rather than organic humor, suggesting a director more comfortable with technical execution than comedic instinct.

The Cultural Context Problem

Back to the Beach arrives at a particularly interesting moment in American cultural history. The 1980s represented a period of intense nostalgia for seemingly simpler times, with television shows like Happy Days and The Wonder Years mining similar emotional territory. The Reagan era’s emphasis on traditional family values and optimistic patriotism created an audience hungry for entertainment that celebrated American innocence and generational continuity.

Within this context, Back to the Beach should have been perfectly positioned for success. It offered familiar characters, recognizable values, and the comfort of seeing beloved performers return to roles that had defined their careers. The film’s modest box office success ($13.1 million against a $12 million budget) suggests that some audiences found exactly what they were looking for in this nostalgia package.

However, the cultural moment that made the film possible also highlighted its limitations. By 1987, the original beach party movies had been dead for over twenty years, and their cultural relevance had been preserved primarily through late-night television reruns and pop culture archaeology. The film’s humor assumes a level of familiarity with 1960s surf culture that many viewers simply didn’t possess, creating comedy that worked only for a specific demographic of a specific age.

The Gentle Disappointment Factor

What makes Back to the Beach particularly frustrating is how close it comes to working within its own limited parameters. The film clearly understands its source material and demonstrates genuine affection for the characters and world it’s revisiting. The production values are adequate, the performances are committed, and the basic concept has merit. These aren’t the hallmarks of cynical cash-grab filmmaking but rather earnest attempt to create something that honors its inspirations.

The problem lies in execution rather than intention. The film’s comedy relies too heavily on recognition humor and celebrity cameos, creating entertainment that feels more like a reunion special than a genuine movie. The pacing suffers from uncertainty about whether it’s primarily a comedy, a musical, or a family drama, resulting in tonal inconsistency that undermines all three approaches.

Most critically, the film never finds its own voice distinct from its source material. Instead of using the beach party format as a launching pad for contemporary comedy, Back to the Beach treats it as a museum piece to be carefully preserved rather than creatively reimagined. The result feels more like archaeological reconstruction than living entertainment.

Critical Reception and Audience Response

The critical response to Back to the Beach revealed interesting divisions about the value of nostalgia-based entertainment. Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel famously gave the film their “two thumbs up” rating, comparing it favorably to Grease and praising its good-natured approach to its source material. Their positive review reflected appreciation for the film’s earnest attempt to recapture innocent entertainment in an era of increasingly cynical comedy.

Other critics were less enthusiastic, viewing the film as evidence of Hollywood’s creative bankruptcy and over-reliance on recycled properties. The 78% positive rating on Rotten Tomatoes suggests that reviewers generally found the film harmless and occasionally charming, even if they didn’t consider it particularly innovative or memorable.

The audience response seems to have divided along generational lines. Viewers with personal connections to the original beach party movies found comfort in seeing beloved characters return, while younger audiences struggled to connect with humor that assumed familiarity with cultural references from before their time. This demographic split highlights one of the fundamental challenges facing nostalgia-based entertainment: the line between honoring the past and being trapped by it.

The Missed Opportunity Syndrome

Perhaps the most disappointing aspect of Back to the Beach is how thoroughly it wastes its considerable potential. The concept of former beach party stars navigating middle-aged suburbia contains genuine comedic possibilities that the film never explores. What does it mean for the “Big Kahuna” to become a car salesman? How does a woman who embodied youthful innocence adapt to the realities of parenting teenagers? These questions could have supported sharp social comedy or touching family drama.

Instead, the film settles for surface-level gags about aging and predictable conflicts between generations that resolve themselves through the magical power of mutual understanding and group singing. It’s comedy that mistakes wholesomeness for wit and assumes that good intentions can substitute for actual insight.

The musical elements suffer from similar problems. Rather than integrating songs organically into the narrative or using them to advance character development, the film treats them as obligatory interludes that happen because beach party movies are supposed to include musical numbers. The result feels more like a concert film interrupted by plot rather than a musical comedy that uses song to enhance storytelling.

Why Back to the Beach Earns Its Spot at Number 40

Back to the Beach lands at number 40 on my worst movies list not because it’s aggressively bad, but because it represents a particularly frustrating form of creative timidity. This is a film that had access to beloved characters, talented performers, adequate resources, and a concept with genuine potential, yet produces something that feels more like a corporate reunion than actual entertainment.

The film demonstrates how good intentions and nostalgic affection can’t overcome fundamental storytelling problems. While the cast and crew clearly care about the source material and want to honor its legacy, they never find a way to make that legacy relevant to contemporary audiences beyond simple recognition factors.

Most critically, Back to the Beach illustrates the difference between homage and creativity. The film succeeds at recreating the surface elements of 1960s beach party movies but fails to understand what made those films work for their original audiences or how those elements might be adapted for different times and sensibilities.

The movie’s reliance on celebrity cameos and recognition humor reveals a fundamental uncertainty about its own entertainment value. When a film needs constant external validation through familiar faces and nostalgic references, it suggests a lack of confidence in its core material that no amount of good-natured charm can overcome.

The Bottom Line

Back to the Beach succeeds as a nostalgic curiosity but fails as entertainment that can stand independent of its historical context. It’s a film that will likely satisfy viewers with deep personal investment in its source material while leaving everyone else wondering why they spent 92 minutes watching a private joke told by people who seem more amused than amusing.

The film represents everything both appealing and problematic about nostalgia-based entertainment. While there’s genuine warmth in seeing beloved performers return to iconic roles, that warmth can’t substitute for actual creativity or insight. Back to the Beach proves that sometimes the past is better left as fond memory rather than contemporary revival.

For viewers seeking either sharp comedy or meaningful family entertainment, Back to the Beach offers neither. It’s a film that mistakes familiarity for quality and assumes that good intentions can overcome poor execution. While it’s certainly not the worst movie ever made, it earns its place on this list by demonstrating how thoroughly a film can waste its potential while maintaining an aggressively pleasant demeanor.

In the end, Back to the Beach feels less like a movie and more like an extended commercial for memories that were probably better than the original films deserved. It’s entertainment that exists primarily to make viewers feel good about things they remember rather than to create new reasons for feeling good. For those of us who prefer our comedy to actually be funny and our nostalgia to serve something larger than itself, Back to the Beach represents a missed opportunity wrapped in good intentions and tied with a bow made of celebrity cameos.

Next week on Movie Monday, we’re trading beach blanket nostalgia for animated Disney magic as we examine The Jungle Book, taking a break from my 100 Worst list to prove I don’t have to be so critical all the time. Join me on January 5th as we explore Disney’s adaptation of Rudyard Kipling’s classic came to life on the big screen. Until then, remember: not every beloved property needs to be revived, and sometimes the most loving tribute is knowing when to leave well enough alone.

What are your thoughts on Back to the Beach? Did you find genuine charm in Frankie and Annette’s return to their beach party roots that I missed, or do you agree that nostalgia alone can’t carry a film? Share your experiences in the comments below—I’d particularly love to hear from viewers who have personal connections to the original beach party movies and how this revival compared to your memories of the source material.

Never heard of it, but I don’t really follow beach movies.

LikeLiked by 1 person