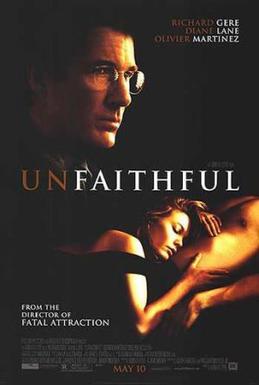

Unfaithful

2002

Directed by Adrian Lyne

Welcome back to Movie Monday, where we continue our relentless march through my personal countdown of the 100 worst movies I’ve ever endured. This week brings us to number 41: Unfaithful, a 2002 erotic thriller that manages the impressive feat of making adultery—one of humanity’s most dramatically fertile subjects—feel about as compelling as watching someone organize their sock drawer. It’s a film that takes 124 minutes to tell a story that could have been resolved with a five-minute conversation between mature adults, but then again, mature adults wouldn’t have given us this exercise in expensive tedium. As always, this reflects my deeply personal perspective—if you found genuine passion and psychological insight in this suburban melodrama, then we experienced entirely different films.

I encountered Unfaithful during those post-college years when you’ll watch almost anything with friends, armed with pizza and the naive belief that any movie starring Richard Gere couldn’t be completely terrible. We were wrong. Sitting through this film felt like being trapped in someone else’s marriage counseling session—uncomfortable, voyeuristic, and ultimately pointless since everyone involved seems determined to make the worst possible decisions at every turn.

The film arrives courtesy of Adrian Lyne, a director whose entire career appears to be built on exploring the various ways attractive people can destroy their lives through sexual indiscretion. From Fatal Attraction to Indecent Proposal, Lyne has carved out a remarkably consistent niche: what happens when well-off, conventionally attractive people make spectacularly poor choices? Unfaithful fits this template so perfectly it might as well have been generated by an algorithm designed to predict Lyne’s next project.

When Moral Complexity Becomes Moral Vacancy

The fundamental problem with Unfaithful isn’t its technical execution—though we’ll get to those issues—but its complete inability to justify its own existence. The film presents itself as a sophisticated exploration of marriage, desire, and consequence, but delivers something closer to an extended public service announcement about why you shouldn’t cheat on your spouse. It’s moral messaging disguised as psychological thriller, and it succeeds at neither.

The story follows Connie Sumner (Diane Lane), a suburban housewife who quite literally stumbles into an affair with Paul Martel (Olivier Martinez), a younger book dealer she meets during a shopping trip gone wrong. What begins as a chance encounter—complete with the kind of meet-cute that would feel contrived in a romantic comedy—escalates into a full-blown affair that threatens to destroy her marriage to Edward (Richard Gere) and their comfortable life in Westchester County.

On paper, this setup contains all the ingredients for compelling drama. The breakdown of a marriage, the psychology of infidelity, the collision between desire and responsibility—these are themes that have fueled great literature and cinema for generations. Unfortunately, Unfaithful approaches these weighty subjects with all the subtlety of a sledgehammer wrapped in expensive cinematography.

The film’s treatment of Connie’s initial attraction to Paul feels particularly false. We’re supposed to believe that this woman, married to Richard Gere and living in what appears to be matrimonial paradise, is so starved for excitement that a brief encounter with a French book dealer sends her into a sexual frenzy. The script provides no real foundation for her dissatisfaction beyond vague hints that her marriage has grown routine—a complaint so universal and minor that it hardly justifies the destruction that follows.

Performance Problems and Character Failures

Diane Lane received widespread critical acclaim for her performance as Connie, earning an Academy Award nomination and numerous other accolades. Ironically, her committed, naturalistic portrayal might be part of what makes the film so frustrating to watch. Lane brings genuine vulnerability and complexity to a character who, as written, doesn’t deserve such thoughtful treatment.

Lane’s performance forces us to sympathize with someone making choices that are not just morally questionable but actively harmful to everyone around her. She makes Connie feel like a real person rather than a moral object lesson, which only makes her behavior more infuriating. When an actor succeeds too well at making a fundamentally unsympathetic character sympathetic, the result can be more unsettling than if they’d simply played the role as written.

Richard Gere, meanwhile, delivers exactly the kind of performance you’d expect from Richard Gere circa 2002—smooth, reliable, and utterly predictable. Edward Sumner feels less like a character than a collection of “good husband” characteristics assembled by a committee. He’s successful, attentive, loving, and devoted to his family, which makes Connie’s betrayal feel even more inexplicable. Gere brings his usual charm to the role, but the script gives him little to work with beyond serving as the noble victim of his wife’s poor judgment.

Olivier Martinez faces perhaps the most challenging task as Paul, the object of Connie’s desire who must somehow justify the destruction of an entire family. Martinez certainly looks the part—brooding, exotic, effortlessly sensual in that particular way that only works in movies—but Paul as written is more fantasy than human being. He’s less a character than a walking midlife crisis, designed to represent everything that Edward supposedly isn’t: spontaneous, passionate, dangerous, and French.

Technical Proficiency Without Purpose

From a purely technical standpoint, Unfaithful represents competent filmmaking. Adrian Lyne knows how to construct a scene, Peter Biziou’s cinematography captures both the sterile perfection of suburban life and the sultry atmosphere of the affair, and Anne V. Coates’ editing maintains narrative momentum even when the story itself threatens to collapse under the weight of its own implausibility.

The film’s visual language effectively contrasts Connie’s two worlds—the muted, controlled palette of her Westchester home against the warm, chaotic textures of Paul’s SoHo apartment. These environments feel genuinely distinct, helping to establish the psychological geography of Connie’s double life. Lyne and his collaborators understand how to create atmosphere, and Unfaithful certainly looks and sounds like a serious film about serious subjects.

Unfortunately, technical competence can’t overcome fundamental storytelling problems. The film’s pacing suffers from an inability to decide whether it wants to be a character study or a thriller. The first half moves with the deliberate pace of psychological drama, exploring Connie’s growing obsession with methodical detail. The second half accelerates into thriller territory, complete with murder, investigation, and moral reckoning, but this shift feels jarring rather than organic.

The investigation subplot, featuring detectives who discover Paul’s body and trace connections back to the Sumner family, introduces elements that feel borrowed from entirely different genres. These scenes work adequately on their own terms, but they exist in uncomfortable tension with the more intimate domestic drama that comprises most of the film’s runtime.

The Affair with Affairs

Perhaps the most telling aspect of Unfaithful is how it fits into Adrian Lyne’s broader obsession with infidelity as dramatic subject matter. Fatal Attraction, Indecent Proposal, 9½ Weeks—Lyne’s filmography reads like a catalog of relationships under sexual and emotional duress. While this consistency could indicate artistic focus, it more often suggests creative limitation.

Lyne approaches adultery with the fascination of someone who finds the subject inherently dramatic rather than someone who has genuine insights to offer about it. His films treat infidelity as exotic and dangerous rather than examining it as a common human failing with complex psychological roots. The result is cinema that sensationalizes rather than illuminates, that mistakes titillation for profundity.

Unfaithful suffers particularly from this approach because it takes itself so seriously while offering so little genuine insight. The film presents Connie’s affair as both inevitable consequence of marital stagnation and inexcusable betrayal of family trust, but never commits fully to either interpretation. This ambivalence might work in a more sophisticated treatment, but here it feels like uncertainty rather than complexity.

The Problem with Moral Neutrality

The film’s greatest failure lies in its attempt to remain morally neutral about behavior that demands moral judgment. Unfaithful wants to present Connie’s affair as understandable while acknowledging its destructive consequences, but this middle-ground approach satisfies no one. Viewers looking for genuine psychological insight get surface-level treatment, while those seeking moral clarity get muddy relativism.

The script goes to considerable lengths to establish Edward as a loving, attentive husband and father, which makes Connie’s betrayal feel particularly inexcusable. Yet the film also asks us to understand her perspective, to see her affair as an awakening rather than simply selfish destructiveness. This balancing act might work if the film provided sufficient foundation for Connie’s dissatisfaction, but her motivations remain frustratingly vague throughout.

The climactic revelation and aftermath feel particularly unsatisfying because they resolve nothing meaningful. Edward’s discovery of the affair and his violent response escalate the stakes without deepening our understanding of any character. The final scenes, which suggest possible reconciliation or at least mutual understanding, feel unearned given everything that’s preceded them.

Critical Reception and Cultural Impact

Despite mixed critical reviews, Unfaithful achieved considerable commercial success, grossing over $119 million worldwide against its $50 million budget. This success largely rode on Diane Lane’s acclaimed performance and the film’s marketing as a sophisticated adult drama in an era when such films were becoming increasingly rare in mainstream cinema.

The critical response split predictably along lines that reflected viewers’ tolerance for the subject matter and their assessment of the film’s artistic merits. Supporters praised Lane’s performance and Lyne’s visual sophistication, while detractors criticized the film’s moral vacancy and predictable plotting. The Academy Award nomination for Lane provided institutional validation, but couldn’t overcome the fundamental storytelling problems that plague the entire enterprise.

The film’s cultural impact has been minimal, remembered primarily for Lane’s performance rather than any particular insight or innovation. Unlike Lyne’s earlier Fatal Attraction, which sparked genuine cultural conversation about sexual politics and personal responsibility, Unfaithful generated little discussion beyond recognition of its technical competence and lead performance.

The Emptiness of Beautiful People Making Ugly Choices

What ultimately makes Unfaithful so frustrating is how thoroughly it wastes its considerable resources. The film features talented performers, skilled craftspeople, and source material with genuine dramatic potential, yet produces something that feels both overwrought and undercooked. It’s a movie that mistakes moral ambiguity for moral complexity, that confuses psychological realism with psychological insight.

The film’s fixation on surface details—the expensive homes, designer clothes, and carefully art-directed adultery—reveals a fundamental shallowness that no amount of technical polish can disguise. Unfaithful is less interested in exploring why people cheat than in showing how beautifully lit such exploration can be.

Perhaps most condemningly, the film takes a subject that should generate genuine emotional response—the betrayal of marriage vows and family trust—and renders it inert through overproduction and under-thinking. By the time Edward makes his climactic discovery and violent response, we’re too exhausted by the preceding tedium to care about the consequences.

Why Unfaithful Earns Its Spot at Number 41

Unfaithful lands at number 41 on my worst movies list because it represents a particularly aggravating form of cinematic failure—the well-made bad movie. This isn’t a film that fails through incompetence or lack of resources, but through a fundamental misunderstanding of its own purpose and potential.

The film demonstrates how technical proficiency and committed performances can’t overcome a script that has nothing meaningful to say about its ostensibly profound subject matter. It’s a movie that exists because adultery is considered inherently dramatic, not because the filmmakers had any particular insight to offer about human relationships or moral responsibility.

Most frustratingly, Unfaithful takes material that could have supported genuine psychological drama and reduces it to expensive melodrama. The film’s success at the box office and Lane’s award recognition suggest that audiences were hungry for sophisticated adult entertainment, but this particular effort serves up sophistication as mere aesthetic rather than substance.

The film also exemplifies the kind of moral relativism that mistakes non-judgment for wisdom. By refusing to take a clear position on Connie’s behavior, the film doesn’t achieve complex moral understanding but rather moral vacancy. Sometimes subjects demand moral clarity rather than moral neutrality, and Unfaithful fails to recognize this distinction.

The Bottom Line

Unfaithful succeeds as an exercise in filmmaking craft but fails utterly as cinema that matters. It demonstrates that beautiful people making terrible choices, when photographed expensively and performed competently, can still produce something fundamentally hollow and unsatisfying.

The film represents everything wrong with a certain strain of “adult” filmmaking that mistakes subject matter maturity for actual maturity of treatment. Having characters discuss weighty themes and face serious consequences doesn’t automatically create serious cinema, and Unfaithful proves that surface sophistication can’t compensate for core emptiness.

For viewers who demand that their entertainment actually entertain, or that their moral dramas provide genuine moral insight, Unfaithful offers neither. It’s a film that takes 124 minutes to tell a story that most viewers will have figured out in the first twenty, then spends the remaining time confirming that everyone involved has learned nothing meaningful from their expensive misery.

In the end, Unfaithful feels less like a movie and more like an elaborate justification for behavior that needs no cinematic validation. It’s a film that asks us to find profundity in selfishness and complexity in simple moral failure. For those of us who prefer our entertainment to actually have something worthwhile to say, Unfaithful represents time that could have been much better spent watching almost anything else.

Next week on Movie Monday, we’re trading suburban infidelity for beach blanket nostalgia as we examine Back to the Beach, a film that proves even the most lighthearted material can still manage to wash up as cinematic driftwood. Join me on December 29th as we explore how 1980s Hollywood managed to make Frankie Avalon and Annette Funicello’s return to their beach party roots feel less like nostalgic fun and more like a cultural relic that should have stayed buried in the sand. Until then, remember: not every story about forbidden attraction needs to be told, and some moral complexities are really just moral simplicities wearing expensive costumes.

What are your thoughts on Unfaithful? Did you find psychological depth in Connie’s journey that I missed, or do you agree that the film’s moral neutrality undermines any potential insight? Share your experiences in the comments below—I’d particularly love to hear from viewers who connected with the film’s treatment of marriage and infidelity, and what specifically resonated with your viewing experience.

Finally a movie I haven’t seen! Though I have heard of Unfaithful and will probably prioritize it for any movies I have left about affairs.

LikeLiked by 1 person