1951

Directed by Ben Sharpsteen, Clyde Geronimi, Wilfred Jackson, Hamilton Luske

Welcome back to Movie Monday! Since it’s the first Monday of the month, we’re taking a well-deserved break from my list of cinematic atrocities to refresh our palates with some classic Disney animation. Think of it as a mental sorbet between courses of bad movie slop.

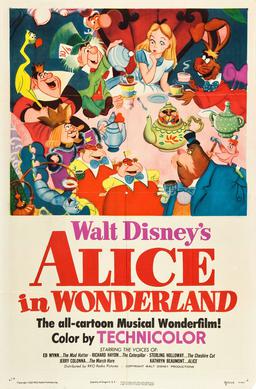

Today, we’re tumbling down the rabbit hole into Walt Disney’s 1951 adaptation of Alice in Wonderland, a film that proved to be surprisingly divisive in its day but has since earned its place in the Disney canon.

A Rocky Start in Wonderland

Walt Disney had a long and complicated relationship with Alice. His fascination with Lewis Carroll’s work dated back to his Kansas City days in 1923, when he produced a short called Alice’s Wonderland featuring a live-action girl interacting with an animated world. That short’s failure might have been an omen – Disney’s feature-length Alice would take nearly three decades to materialize, encountering obstacles and revisions at every turn.

The project first gained momentum after Snow White‘s massive success in 1937, but Disney’s initial approach was ambitious: he envisioned a live-action/animated hybrid starring Mary Pickford as Alice. Fortunately (or unfortunately, depending on how much you enjoy post-Roger Rabbit fever dreams), Paramount Pictures secured the film rights for their own live-action version, forcing Disney to shelve the project.

When Disney returned to Alice in the 1940s, he brought in British author Aldous Huxley – yes, THAT Aldous Huxley – to write a script that somehow involved Lewis Carroll being persecuted for writing Alice, Queen Victoria saving the day, and actress Ellen Terry as a supporter of Carroll. If this sounds like a bizarre Victorian melodrama, that’s because it was. Disney wisely concluded that maybe a fully animated feature would be simpler.

Mad Animation for a Mad World

Once production began in earnest, Alice in Wonderland became something of a free-for-all experiment. Unlike the cohesive designs of Cinderella or the storybook charm of Snow White, Alice was a playground for Disney’s artists to explore their wildest visual impulses. Background artist Mary Blair’s influence is evident throughout, with her bold, modernist colors and shapes giving Wonderland a distinctly contemporary edge compared to the studio’s previous fairy tale adaptations.

The film’s animation team included all of Disney’s legendary Nine Old Men, each bringing their own interpretation to various characters. Ward Kimball later complained about the “too many cooks” problem – with multiple directors each trying to make their sequences the biggest and craziest in the show, the film ended up with a somewhat scattered energy. This actually works surprisingly well for Carroll’s episodic narrative, though it meant sacrificing the emotional throughline that had made Snow White and Cinderella resonate with audiences.

A Musical Mashup of Madness

Alice boasts more songs than any other Disney animated feature – over 30 were written, with many making it into the film for just a few seconds. This creates a musical landscape as fragmented as Wonderland itself. While some songs like “I’m Late” and “The Unbirthday Song” have become classics, others appear and vanish so quickly you’ll wonder if they were ever there at all.

The musical approach reflects the film’s overall strategy: throw everything at the wall and see what sticks. Some of the most memorable moments – like the Mad Tea Party and “All in the Golden Afternoon” with the flowers – work because they fully embrace their nonsensical nature. Others, like the Jabberwocky-inspired “Twas Brillig,” show how the filmmakers cleverly adapted Carroll’s poetry into Disney’s musical language.

Critical Disaster, Cultural Triumph

When Alice finally premiered in 1951, critics were not amused. British reviewers were particularly harsh, accusing Disney of “Americanizing” a beloved piece of English literature. American critics weren’t much kinder, with many finding the film lacking the heart and warmth of Disney’s previous features. Walt himself later admitted the film failed because it had no heart – apparently, existential nightmare logic doesn’t play well with mainstream audiences seeking emotional catharsis.

The film lost money on its initial release, becoming the studio’s first real box office disappointment. Disney buried it for years, only allowing it to air once on television in 1954. But here’s where things get interesting: when the film was re-released in 1974, it found an entirely new audience. College students embraced its psychedelic visuals and dreamlike logic, turning Alice into a cult classic. Disney even marketed it as a film in tune with the “psychedelic times,” using ads that referenced Jefferson Airplane’s “White Rabbit.”

Legacy and Influence

Today, Alice in Wonderland stands as one of Disney’s most unique animated features. Its influence can be seen everywhere from theme park attractions (the teacups ride being arguably the most perfect match of form and content in Disney’s parks) to the visual language of later experimental Disney work like The Black Cauldron and Atlantis: The Lost Empire.

The film’s rehabilitation is complete: it now holds an 84% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, with critics praising its “surreal and twisted images” that once confused audiences. Modern viewers appreciate what 1951 audiences couldn’t: Alice doesn’t need to be warm and cuddly to be wonderful. Sometimes, being wonderfully weird is enough.

Final Thoughts

Watching Alice in Wonderland today, it’s hard to understand why contemporary critics were so baffled. Yes, it lacks the emotional core of Dumbo or the storybook structure of Cinderella. But in its place, we get something far more interesting: a visual feast that captures the genuine strangeness of Carroll’s original work. The film’s scattered approach actually strengthens its dreamlike atmosphere, making it feel more like a series of vivid hallucinations than a traditional narrative.

If you haven’t revisited Alice recently, it’s worth tumbling back down that rabbit hole (you can find it on Disney+). Just remember – unlike my usual bad movie fare, this one’s meant to make your head spin.

Join me next week when we return to our regularly scheduled program of cinematic disasters. Until then, stay curious!

Curiouser and curiouser? Unlike most Disney classics, I have a far stranger history with Alice in Wonderland. Whenever I watched it as a child, only a few key moments ever stood out to me. Alice following the White Rabbit down the rabbit hole, the tea party, Cheshire Cat, and the ending with the Queen of Hearts. I had trouble retaining the rest of the movie, because it’s just so chaotic. Years later I found much more appreciation for its commitment to absurdity. I’m glad modern audiences did the same.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ever try reading the book? It’s like stepping into someone’s insane acid trip.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I haven’t read Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, but I imagine that’s exactly how it feels.

LikeLiked by 1 person