In the pantheon of action cinema, few films have left as indelible a mark as John McTiernan’s 1988 masterpiece Die Hard. What began as a relatively modest summer release with modest expectations transformed not only the trajectory of Bruce Willis’s career but revolutionized how Hollywood approached action films for decades to come. More than 35 years after its release, Die Hard remains the blueprint that countless action films have attempted to replicate—some successfully, most not. Its influence extends far beyond simple imitation; it fundamentally altered our understanding of what an action hero could be and how an action narrative could unfold.

And yes, it’s absolutely a Christmas movie—but we’ll get to that later.

The Vulnerable Hero: Bruce Willis as John McClane

Prior to Die Hard, the action genre was dominated by muscle-bound demigods. Arnold Schwarzenegger in Commando could mow down entire armies single-handedly. Sylvester Stallone’s Rambo was an indestructible force of nature. These heroes were essentially superheroes without capes—physically imposing, virtually invulnerable, and emotionally distant. They didn’t bleed much, they rarely showed fear, and they certainly didn’t cry.

Enter John McClane.

When 20th Century Fox cast Bruce Willis as the lead in Die Hard, it was considered an enormous risk. Willis was known primarily for his comedic role opposite Cybill Shepherd in the romantic comedy television series Moonlighting. He had only one feature film under his belt—the moderately successful comedy Blind Date (1987). At the time, there was a clear distinction between film and television actors, and Willis’s $5 million salary was seen as exorbitant for someone with his limited film experience.

The studio’s gamble paid off spectacularly, in large part because Willis brought something entirely new to the action genre: vulnerability.

McClane isn’t a superhuman commando or a specially trained assassin—he’s just a regular cop from New York who happens to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. Throughout the film, he’s constantly injured, exhausted, and genuinely frightened. In one of the most iconic scenes, McClane removes glass shards from his bare feet after walking through broken glass, wincing in pain as blood pools on the bathroom floor. This moment of weakness—something that would have been unthinkable for a Schwarzenegger or Stallone character—made McClane instantly relatable to audiences.

“Even though he’s a hero, he is just a regular guy,” Willis said of the character. “He’s an ordinary guy who’s been thrown into extraordinary circumstances.”

This vulnerability extends beyond the physical. McClane is emotionally vulnerable as well. He’s struggling with a failing marriage. When he believes he might die, he breaks down and asks Al Powell (Reginald VelJohnson) to tell his wife that he’s sorry—a raw emotional moment rarely seen in action films of the era. Willis’s performance showed that an action hero could be funny, scared, and emotional while still being ultimately heroic.

The genius of Willis’s portrayal is that McClane’s one-liners don’t come from a place of superiority or confidence like many action heroes before him. Instead, they emerge as nervous reactions to the extreme situations he faces. His famous catchphrase—”Yippee-ki-yay, motherf****r”—isn’t delivered as a triumphant battle cry but as a defiant response to stress.

The Confined Setting: Nakatomi Plaza as Character

Another revolutionary aspect of Die Hard was its setting. While previous action films often spanned cities, countries, or even continents, Die Hard confined almost all of its action to a single building—the fictional Nakatomi Plaza (actually Fox Plaza in Century City, Los Angeles).

This confined setting created a claustrophobic tension that pervaded the entire film. It also grounded the action in a sense of reality that had been missing from the more fantastical action films of the era. McClane couldn’t call in reinforcements or escape to regroup—he was trapped, creating a pressure-cooker environment that amplified every encounter.

Cinematographer Jan de Bont used handheld cameras to film closer to the characters, creating what he called a more cinematic “intimacy.” This technique brought viewers into McClane’s space, making them feel the urgency and danger of his situation in a visceral way. The building itself became a character, with McClane navigating its ventilation shafts, elevator shafts, and unfinished floors like a modern-day labyrinth.

Production designer Jackson De Govia chose Fox Plaza specifically because it was distinctive enough to be a character on its own. The surrounding city could be seen from within the building, enhancing the realism and allowing for establishing shots as McClane approaches. This meticulous attention to the physical space of the action set a new standard for how action films utilized their environments.

A Perfect Villain: Alan Rickman’s Hans Gruber

Just as Willis redefined the action hero, Alan Rickman’s portrayal of Hans Gruber revolutionized the action villain. Prior to Die Hard, action antagonists tended to be either eccentric madmen or bland, one-dimensional figures. Gruber was something entirely new: intelligent, charming, sophisticated, and genuinely threatening.

Rickman, in his first screen role at age 41, brought a theatrical gravitas to Gruber. He wasn’t just physically threatening (though he was certainly dangerous); he was intellectually challenging. Gruber’s plans were meticulous, his adaptability impressive. When he encounters McClane, he quickly improvises by pretending to be a hostage, showcasing his quick thinking.

The dynamic between McClane and Gruber established a new template for hero-villain relationships in action cinema. They are perfect foils for each other: McClane is working class, American, and improvisational; Gruber is educated, European, and methodical. Their contrast creates a tension that extends beyond simple good versus evil into a clash of worldviews and approaches.

Their limited direct interaction makes their confrontations all the more impactful. When they finally meet face-to-face near the film’s conclusion, the payoff is enormous—a culmination of the cat-and-mouse game they’ve been playing throughout the film.

Technical Innovations: Action with Consequence

Die Hard also transformed how action sequences were filmed and presented to audiences. Unlike the bloodless, consequence-free action of many preceding films, McTiernan and his team emphasized the physical toll of violence.

Stunt work took on new importance, with Willis performing many of his own stunts, including jumping from the rooftop with a firehose wrapped around his waist as a massive wall of flame exploded behind him. This commitment to physical authenticity helped sell McClane’s ordeal to audiences.

The film’s sound design also broke new ground. Willis suffered a permanent two-thirds hearing loss in his left ear from firing blank cartridges close to his head during filming—a testament to the production’s commitment to realistic gunfire sounds rather than the often cartoonish sound effects used in other action films.

Michael Kamen’s score incorporated classical pieces like Beethoven’s 9th Symphony (“Ode to Joy”) to underscore the villains’ actions, creating a sophisticated sonic landscape that elevated the film above typical action fare. The music references build to a performance of the symphony when Gruber finally accesses the Nakatomi vault, a subtle reinforcement of the film’s thematic elements.

The “Die Hard on a…” Legacy

Perhaps the clearest evidence of Die Hard‘s revolutionary impact is the number of films that followed its template so closely that they were described as “Die Hard on a…” by critics and marketers alike.

This formula became shorthand for a lone, everyman hero who must overcome an overwhelming opposing force in a relatively small and confined location. Some notable examples include:

- Under Siege (1992) – “Die Hard on a battleship”

- Cliffhanger (1993) – “Die Hard on a mountain”

- Speed (1994) – “Die Hard on a bus”

- Con Air (1997) – “Die Hard on a plane”

- Air Force One (1997) – “Die Hard on the president’s plane”

Willis himself once recalled being pitched a film that was “Die Hard in a skyscraper.” He wryly noted that he was “sure it had already been done.”

This imitation extended beyond explicit “clones” into the broader action genre. The everyman hero facing overwhelming odds became a staple character type. The confined setting creating tension through limited escape options became a common narrative device. The intelligent, charismatic villain worthy of the hero’s struggle became the new standard.

It wasn’t until the mid-1990s with the advent of CGI-heavy films like Independence Day (1996) and Armageddon (1998) that Hollywood began to move away from the Die Hard template toward more fantastical destruction. Yet even today, when critics praise an action film for its “grounded approach” or “relatable hero,” they’re often invoking comparisons to McClane’s original adventure.

Cultural Impact: “Yippee-ki-yay” and Christmas Debates

Beyond its influence on filmmaking, Die Hard permeated popular culture in ways few action films have managed. McClane’s catchphrase, “Yippee-ki-yay, motherf****r”—inspired by old cowboy lingo including Roy Rogers’s “Yippee-ki-yah, kids”—has become one of cinema’s most recognizable lines, instantly associated with the character and the film.

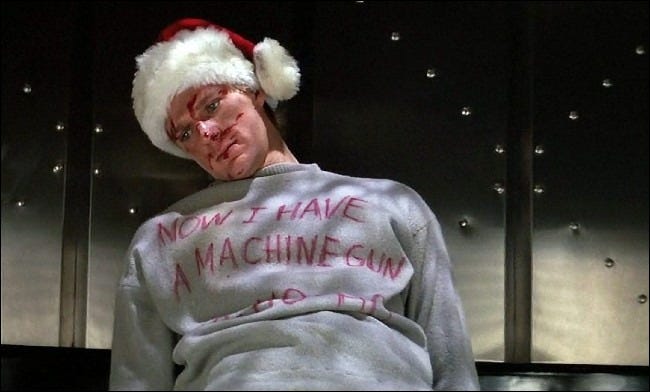

The film’s Christmas setting has sparked one of the most enduring debates in film culture: Is Die Hard a Christmas movie? The answer, as any true film aficionado knows, is an unequivocal yes. The film takes place entirely on Christmas Eve, features numerous Christmas songs (including “Let It Snow” and Run-DMC’s “Christmas in Hollis”), and even includes themes of reconciliation and redemption appropriate to the season. It has become a holiday tradition for many viewers who prefer their Christmas fare with a higher body count.

On the film’s 30th anniversary in 2018, 20th Century Fox settled the debate by releasing a re-edited trailer that portrayed it as a traditional Christmas film, declaring it “the greatest Christmas story ever told.” According to screenwriter Steven E. de Souza, producer Joel Silver had predicted the film would be played at Christmastime for years to come.

In 2017, Die Hard was selected by the United States Library of Congress to be preserved in the National Film Registry for being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant”—a rare honor for an action film. Bruce Willis’s bloodied and sweat-stained undershirt was donated to the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian Institution, cementing its status as a cultural artifact.

The Anti-Hero Evolution

Die Hard arrived at a crucial transitional moment in American culture and politics. The certainties of the Cold War were beginning to dissolve, and the clear-cut heroism of earlier action films no longer resonated with audiences in the same way.

McClane represents a new kind of American hero—one who questions authority and operates outside official structures when necessary, but who still fundamentally believes in protecting innocent people. He’s cynical but not nihilistic, world-weary but not heartless.

This evolution of the action hero reflects broader cultural shifts. The muscular certainty of Rambo gave way to the improvisational vulnerability of McClane, who faces not just external threats but personal failings. His journey to rescue his wife is also a journey to salvage his marriage—a metaphorical battle as important as his literal fight against terrorists.

The film also subtly critiques various American institutions. The police are portrayed as sometimes incompetent, the FBI as dangerously overconfident, the media as unscrupulously self-serving. Yet McClane, as a police officer himself, represents the possibility of individual integrity within flawed systems—a nuanced perspective rarely seen in action films of the era.

Conclusion: The Enduring Blueprint

More than three decades after its release, Die Hard remains the gold standard against which action films are measured. Its perfect blend of character development, confined setting, well-choreographed action, and genuine tension created a template that countless films have followed.

Bruce Willis’s portrayal of John McClane fundamentally changed our expectations of action heroes. After McClane, audiences no longer accepted invincible muscle men as readily; they wanted heroes who could bleed, doubt, fear, and still ultimately triumph through grit and determination rather than superhuman abilities.

The film’s influence extends beyond action cinema into how we think about heroism itself—the idea that ordinary people thrust into extraordinary circumstances can find reserves of courage they didn’t know they possessed.

In the pantheon of films that genuinely changed their genres, Die Hard stands alongside Star Wars, The Godfather, and Psycho—not just an excellent example of its type, but a revolutionary work that transformed what was possible within its category. And yes, it’s definitely a Christmas movie—perhaps the most thrilling Christmas movie ever made.

So the next time you watch John McClane crawl through those ventilation ducts or battle Hans Gruber high above Los Angeles, remember you’re watching more than just an action film—you’re watching the blueprint that redefined an entire genre.

Yippee-ki-yay, indeed.