When DC Comics launched its Earth One line in 2009, the concept seemed straightforward enough: modernize iconic heroes for contemporary audiences with standalone graphic novels that reimagined their origins without the baggage of decades of continuity. J. Michael Straczynski kicked things off with Superman: Earth One in 2010, presenting a Clark Kent who wrestled with career choices and self-doubt before reluctantly becoming a hero. Geoff Johns followed with Batman: Earth One in 2012, giving us a Bruce Wayne who was genuinely inexperienced and prone to mistakes rather than the near-perfect Dark Knight we’d come to expect.

The Earth One line was, to be honest, hit or miss. The Batman graphic novels were pretty decent—Johns and Gary Frank created a grounded, humanized version of the mythos that felt fresh. Superman’s titles were interesting, even if they stumbled in places. The rest? Kind of “meh” in my book.

Then came Grant Morrison.

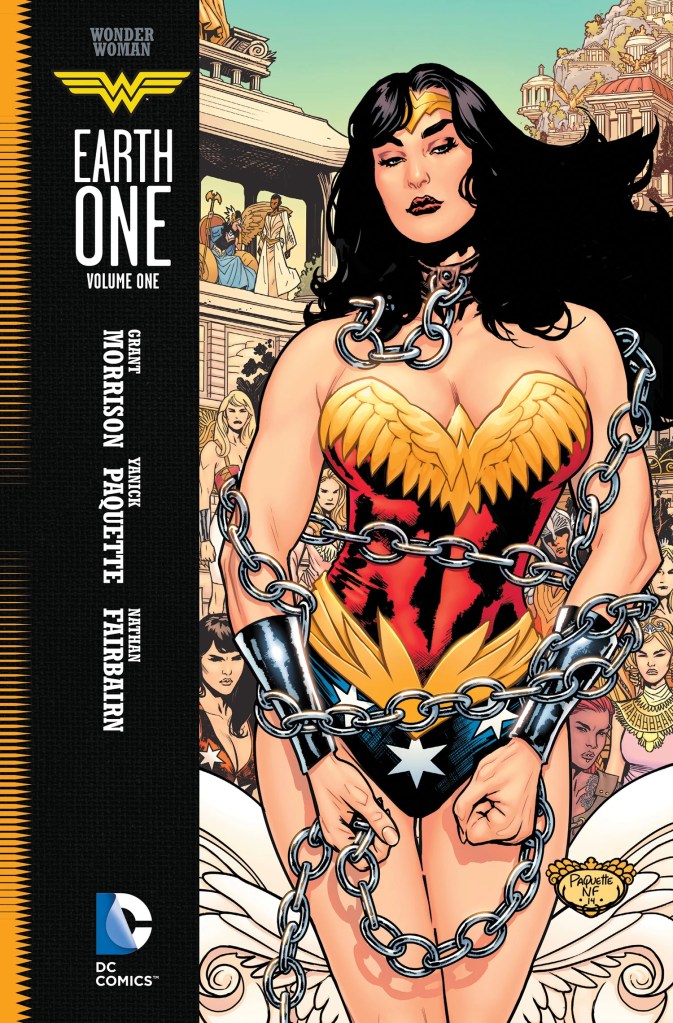

When Wonder Woman: Earth One finally arrived in April 2016—seven years after the line’s inception—it landed like a Greek goddess crashing through the roof of a building. But instead of universal celebration, Morrison and artist Yanick Paquette’s take on Diana sparked immediate controversy. The reason? Morrison didn’t just modernize Wonder Woman. He doubled down on the most uncomfortable, often-overlooked aspects of her Golden Age origins: the obsession with bondage, submission, and the unconventional gender politics that her creator, William Moulton Marston, had baked into the character from day one.

The Return to Marston’s Roots

To understand why Wonder Woman: Earth One proved so divisive, you need to understand where Morrison was coming from. Unlike Straczynski’s Superman or Johns’s Batman, Morrison wasn’t interested in making Wonder Woman more relatable or realistic. He wanted to resurrect the original vision that Marston had for the character in 1941—a vision that subsequent decades of writers had gradually sanitized, downplayed, or outright ignored.

William Moulton Marston—psychologist, polygraph inventor, and polyamorist living with both his wife Elizabeth and their partner Olive Byrne—created Wonder Woman as what he openly called “psychological propaganda for the new type of woman who, I believe, should rule the world.” But Marston’s feminism was… unconventional, to put it mildly. He believed in female superiority, sure, but he also believed that the path to peace lay in what he termed “loving submission”—the idea that people should willingly submit to loving authority rather than assert themselves through violence and dominance.

This philosophy manifested in the early Wonder Woman comics through an absolutely staggering amount of bondage imagery. Diana and her fellow Amazons were constantly being tied up, chained, bound at the wrists, captured, and freed again. Marston even created “Aphrodite’s Law,” which stated that if Wonder Woman’s bracelets were bound together by a man, she would lose her Amazon strength. The subtext wasn’t even really subtext—it was just text that nobody wanted to talk about at PTA meetings.

After Marston’s death in 1947, DC Comics spent decades trying to make people forget about all of that. The bondage themes were quietly dropped. Wonder Woman became more conventional, more “respectable,” more like the other superheroes. By the time we got to George Pérez’s celebrated 1980s reboot, Wonder Woman was reimagined as a peace-loving ambassador from Themyscira, her origins tied to Greek mythology rather than Marston’s peculiar theories about submission and female authority.

Morrison looked at all that sanitization and said, “Nah. Let’s go back.”

The “Loving Submission” Problem

Wonder Woman: Earth One doesn’t shy away from Marston’s original vision—it embraces it completely. The story explicitly presents Themyscira as a society built on the principles of “loving submission” and “Amazonian submission culture.” Diana’s mission in “man’s world” isn’t just to fight injustice; it’s to spread the message of loving submission as an alternative to patriarchal violence and domination.

The graphic novel opens with Hercules capturing and degrading Queen Hippolyta before she seduces him and breaks his neck with her own chains—establishing right away that this isn’t going to be your typical superhero origin. When Diana eventually leaves Themyscira to save Steve Trevor and bring him back to America, she’s put on trial by her fellow Amazons for breaking their laws and consorting with the world of men.

Throughout Volume One, Morrison presents the Amazons as a utopian society that has achieved peace through their submission-based culture—but also as a society that’s isolationist, judgmental toward Diana’s choices, and ultimately willing to attack her for violating their traditions. The visual storytelling by Paquette includes plenty of imagery that recalls Marston’s Golden Age work: Amazons in chains, bondage positions presented as training exercises, and Diana herself frequently bound or restrained.

The kicker comes when Diana discovers that she was actually born from Hercules’s assault on Hippolyta—she’s literally the daughter of patriarchal violence, which adds a whole other layer of uncomfortable complexity to the narrative about submission and authority.

Morrison clearly intended this as a serious exploration of Marston’s ideas. In interviews, both Morrison and Paquette discussed how they wanted to be faithful to the original creator’s vision and examine what an Amazonian society based on those principles would actually look like. The problem is that “loving submission” as a feminist philosophy is… well, it’s a tough sell in 2016.

How Does It Compare to the Other Earth One Books?

If we’re judging Wonder Woman: Earth One against its siblings in the Earth One line, it’s definitely the most ambitious and the most willing to take risks.

Superman: Earth One gave us a Clark Kent who considered becoming a professional athlete or researcher instead of a hero, which was fine but not exactly groundbreaking. The story followed pretty familiar beats—alien invasion forces Clark to reveal himself, he fights a villain with connections to Krypton’s destruction, he joins the Daily Planet. Straczynski’s writing was workmanlike, and while Shane Davis’s art was solid, the whole thing felt like a pitch for the Man of Steel movie more than a truly fresh take on the character. IGN’s Dan Phillips called it “riddled with creative decisions that’ll leave you scratching your head in disbelief,” and criticized Superman for becoming “an angst-ridden cliché with a flimsy moral center.”

Batman: Earth One fared better. Johns and Frank created a Batman who was genuinely learning on the job, making mistakes, struggling with his equipment. The reveal that Mayor Cobblepot was behind the Wayne murders—and that Alfred was a military badass rather than a butler—gave the story some real surprises. It felt like Johns understood what made Batman work while being willing to challenge some assumptions about the character. The characterization was strong, particularly with Harvey Bullock’s journey and the reimagining of supporting characters like Jessica Dent.

Wonder Woman: Earth One stands apart because Morrison wasn’t interested in simply modernizing or humanizing Diana the way Straczynski and Johns did with their characters. Morrison wanted to excavate something stranger and more uncomfortable from the character’s history and force readers to confront it. Whether that’s a feature or a bug depends entirely on your perspective.

The other Earth One books asked: “What if Superman/Batman were more relatable?” Morrison asked: “What if we actually took William Moulton Marston seriously?”

The Critical Reception and Controversy

IGN’s review of Volume One captured the split reaction perfectly: “Wonder Woman: Earth One Volume One is not going to be a comic for everyone. This original graphic novel offers a more provocative take on the iconic heroine, one that returns her to her Golden Age, bondage-obsessed roots and dabbles in material some readers might find uncomfortable.”

And there’s the rub: “uncomfortable” is exactly what Morrison was going for, but uncomfortable doesn’t always translate to good storytelling or effective social commentary.

The book was commercially successful—it hit #1 on The New York Times’ Hardcover Graphic Books Best Seller List—but the critical discourse around it was fascinating. Some readers and critics appreciated Morrison’s willingness to engage with Marston’s original vision, even if they didn’t entirely agree with it. Others found the whole “loving submission” angle to be, at best, a dated feminist philosophy that hadn’t aged well, and at worst, actively regressive.

The fundamental question became: Can you reclaim and rehabilitate Marston’s ideas about submission and female authority for a modern audience? Or are those ideas too rooted in the specific (and frankly weird) sexual politics of the 1940s to translate to contemporary feminism?

Morrison seemed to believe the former. Many readers felt the latter.

Volumes Two and Three: Escalation and Resolution

Volume Two, released in October 2018, doubled down on the provocative elements while adding a plot involving Nazis, mind control, and a villain literally named “Dr. Psycho” who uses post-hypnotic suggestion to control Diana and make her lose her powers and will. The story gets darker—Hippolyta is murdered, Diana is manipulated into declaring war on “man’s world,” and the whole thing becomes a meditation on how patriarchal forces weaponize and corrupt movements for female empowerment.

IGN called Volume Two’s take on the villains “clever” but criticized the “choppy” pacing and lack of resolution. The storyline involving Paula von Gunther—a Nazi who becomes Diana’s idol and later murders Hippolyta because she “loved Diana and wanted to rule with her over man’s world”—added layers of moral complexity that didn’t always land cleanly.

Volume Three, published in March 2021, brought the trilogy to a close with Diana assembling all the Amazonian tribes to face Maxwell Lord’s assault on Paradise Island with his A.R.E.S. battle armors. GeekDad’s Ray Goldfield called it “the most unique and bizarre of the Earth One books,” which feels about right for a series that spent three volumes exploring whether bondage-based utopian feminism could save the world from patriarchal violence.

By the end of the trilogy, Morrison had fully committed to the bit. Diana becomes queen of the Amazons and prepares to bring her message of peace to Man’s World while simultaneously preparing for war. It’s contradictory, messy, and deliberately provocative—very much in keeping with the entire project.

So… Was It Good?

Here’s the thing about Wonder Woman: Earth One: I respect what Morrison was trying to do more than I actually enjoyed reading it.

Morrison is obviously a brilliant writer with a deep understanding of Wonder Woman’s history and a genuine interest in engaging with Marston’s original, deeply weird vision for the character. The artwork by Yanick Paquette is gorgeous—he won the Best Artist Shuster Award in 2017 for Volume One and received nominations for Volume Two. The book clearly has ambition and isn’t content to simply retread familiar ground.

But “loving submission” as the cornerstone of Amazonian culture is a tough concept to build a modern Wonder Woman story around, no matter how thoughtfully you approach it. Marston’s ideas about benevolent female authority and willing submission to loving leadership made a certain kind of sense in his own mind, informed by his background in psychology and his unconventional personal life. But stripped from that specific context and presented to a 21st-century audience raised on third-wave feminism and #MeToo, it lands differently.

The book asks readers to take seriously the idea that a society based on ritualized submission—even loving, consensual submission to female authority—represents a viable feminist utopia. That’s a big ask. It’s asking readers to embrace a vision of feminism that prioritizes different values than most contemporary feminist discourse: submission over assertion, loving authority over egalitarianism, ritual bondage over freedom from constraint.

Some readers found this fascinating. Others found it off-putting or even offensive. I found it… interesting but ultimately unsatisfying. The ideas are provocative, but Morrison never quite convinced me that this vision of Amazonian culture was as enlightened or progressive as the text wanted me to believe it was.

The Larger Question About Wonder Woman

What Wonder Woman: Earth One really highlights is the ongoing struggle to figure out what Wonder Woman should be in the modern era. Unlike Superman (immigrant hero, moral compass, ultimate idealist) or Batman (traumatized genius, dark detective, symbol of fear), Wonder Woman has never quite settled into a definitive modern interpretation that everyone agrees on.

Is she a warrior? A peacemaker? A diplomat? A revolutionary? Depending on which comic run you read or which adaptation you watch, you’ll get different answers. George Pérez made her an ambassador of peace. Brian Azzarello made her the God of War. Greg Rucka emphasized her commitment to truth and compassion. Gail Simone focused on her strength and warrior spirit.

Morrison chose to make her the ambassador of “loving submission,” and while that’s certainly a choice rooted in the character’s history, it’s also one that highlights how difficult it is to build a coherent, compelling modern Wonder Woman on that particular foundation.

The Earth One line was supposed to give creators freedom to reimagine these characters without continuity constraints, to find the essential core of who they are and rebuild from there. Morrison found something essential about Wonder Woman, all right—but whether what he found is something worth building on is another question entirely.

Final Thoughts

Wonder Woman: Earth One is undeniably the most unique and polarizing entry in the Earth One line. It’s more daring than the Superman books, more conceptually ambitious than the Batman books, and more willing to alienate readers by committing fully to a controversial creative vision.

But being daring doesn’t necessarily make it good, and being faithful to William Moulton Marston’s original intentions doesn’t necessarily make it relevant to contemporary readers.

I admire Morrison’s willingness to dig into the weird, uncomfortable parts of Wonder Woman’s history that most writers prefer to ignore. I appreciate the attempt to take Marston’s ideas seriously rather than dismissing them as embarrassing relics of a less enlightened time. And Paquette’s artwork really is stunning throughout all three volumes.

But at the end of the day, I’m not sure Morrison made a convincing case that “loving submission” should be at the heart of Wonder Woman’s mythology in the 21st century. The comic is more interesting as a thought experiment than as a definitive take on the character—a “what if” that’s worth examining but not necessarily worth adopting as the primary lens through which we understand Diana.

Your mileage, as they say, may vary. Some readers have found Wonder Woman: Earth One to be a revelation, a bold reclamation of forgotten feminist philosophy. Others have found it to be a well-intentioned misfire that resurrects ideas better left in the 1940s.

Me? I’m glad Morrison wrote it. I’m glad it exists as part of the conversation about who Wonder Woman is and what she represents. But I’m also glad it exists in its own separate continuity, leaving other writers free to explore different, perhaps less submission-focused interpretations of the Amazon princess.

Sometimes the most interesting experiments are the ones that don’t quite work—and Wonder Woman: Earth One is definitely one of the most interesting experiments in superhero comics in recent years, for better and for worse.